Audio Sample

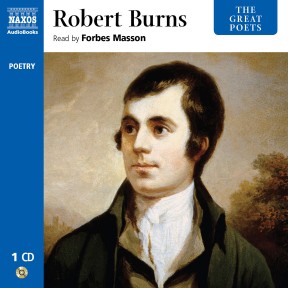

Robert Burns

The Great Poets – Robert Burns

Read by Forbes Masson

selections

The 250th anniversary of the birth of Robert Burns (1759–1796), one of the most popular of poets, is celebrated in 2009. A pioneer of the Romantic movement, works such as A Red, Red Rose, A Man’s a Man for a’ That and the ubiquitous Auld Lang Syne, have made him an international figure. Naxos AudioBooks’ popular Great Poets series marks the anniversary with a CD bringing together all the key works.

-

Running Time: 1 h 18 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-858-2 Cat. no.: NA196812 Download size: 19 MB BISAC: POE005020 Released: January 2009 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

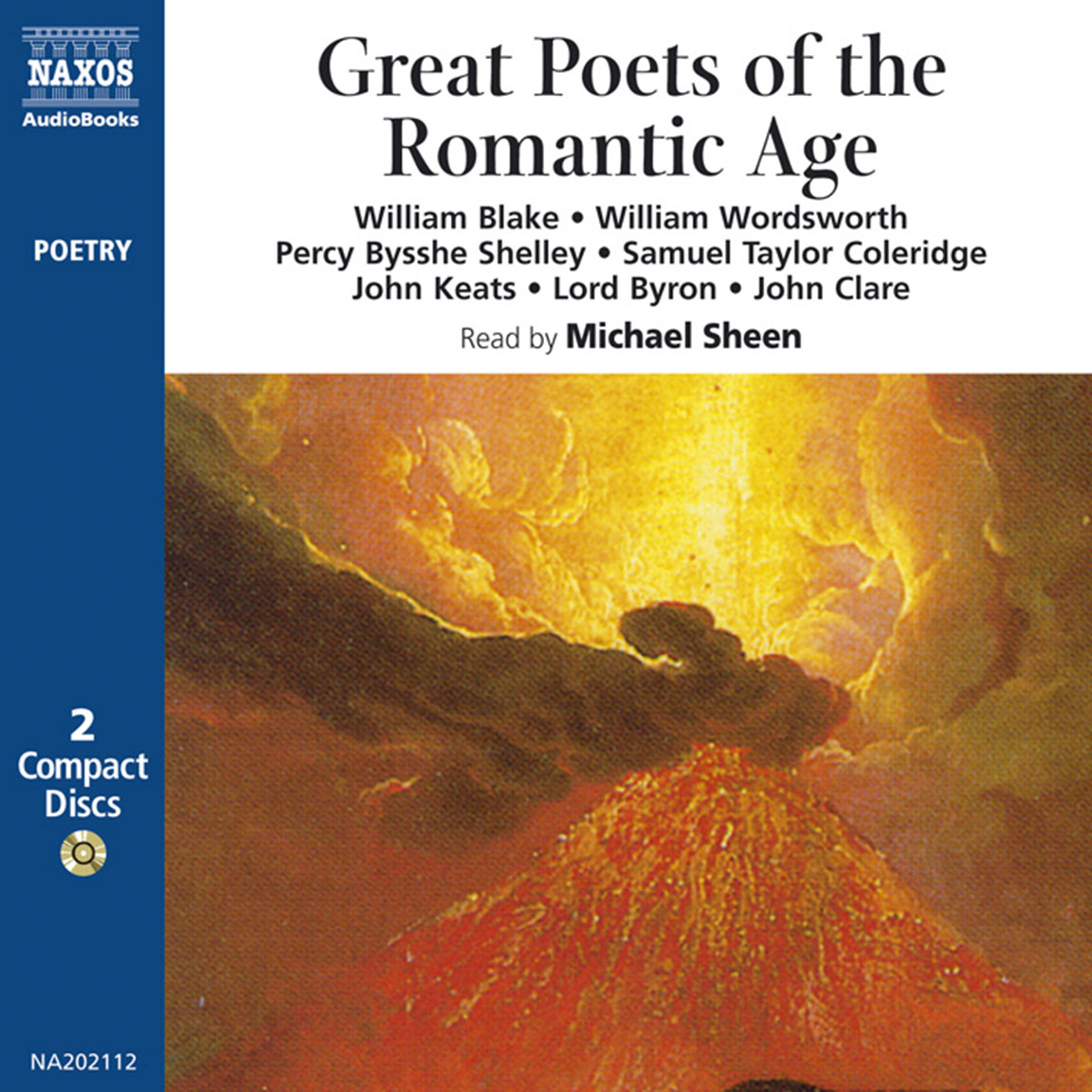

You May Also Enjoy

Included in this title

A Man’s a Man for a’ That

A Red, Red Rose

A Winter Night

Address to a Haggis

Address to the Unco Guid

Ae Fond Kiss

Apology for Declining an Invitation to Dine

Auld Lang Syne

Bessy and her Spinnin’ Wheel

Epistle to a Young Friend

Holy Willie’s Prayer

I’ll Meet Thee on the Lea Rig

Man Was Made to Mourn

My Bonie Mary

My Love She’s but a Lassie Yet

On a Suicide

Robert Bruce’s March To Bannockburn

Such a Parcel of Rogues In A Nation

Tam O’Shanter – A Tale

The Banks o’ Doon

The Cotter’s Saturday Night

From The Jolly Beggars

To a Louse On seeing one on a lady’s bonnet, at church

To a Mouse On turning her up in her nest with the plough

To Mary in Heaven

Booklet Notes

When Robert Burns was born in 1759 America was still a colony and France still had a monarchy. When he died, just 37 years later, America was independent and the French king had been executed. Across two continents, revolution had overturned the Enlightenment establishment – the elegance and precision of the Augustan Age had been overwhelmed by the emotional immediacy of the Romantics. It didn’t stay that way for long, of course:the loss of America didn’t stop Britain colonising aquarter of the globe; and the French returned to emperors and kings within 15 years of the Revolution. Nevertheless there had been a profound shift, and to writers thereafter Robert Burns symbolised the human side of it.

He was the eldest son of a farmer and gardener, William Burness (Robert dropped the extra s in 1786), and Agnes Broun. William believed in knowledge, and after starting his children’s education at a local school he employed a tutor to continue it. As a result, Burns became familiar with literature, albeit English rather than Scottish. He learnt poetry, prose and grammar, and began reading for himself. Another rich source for his imagination came from his mother and her friend Betty Davidson. They would tell stories and sing folksongs of fairy-tales, legends and myths: a mixture of the dramatic, elegiac and romantic; the suggestive, bawdy and erotic.

Robert’s own joie de vivre and energy found an outlet at local dances, despite his father’s opposition. He began composing poetry to the music of the jigs in order to woo the local girls, and he became involved with discussion groups. He joined the Freemasons too, where he became loved as much for his impromptu verses as for his considered ones. After his father died in 1784, his plan with his brother Gilbert to set up a farm became a necessity.

It was 1785 which saw his vain, passionate, loving, arrogant, creative self emerge. Burns began writing a commonplace book. He wrote some of the finest poetry ever to have come from Scotland: The Jolly Beggars, The Cotter’s Saturday Night, Holy Willie’s Prayer and more. He had been actively writing since he was about 10, but it was as if he now found his voice more completely, or it had matured sufficiently, so his immediacy had no sentimentality and his versification no intrusive formality. His work mocked the clergy, called for a kind of revolution, was sublimely descriptive, and painted people with deft and touching humanity. It was also unapologetically in Scottish dialect. But this year marked a turning-point in Burns’s personal life, too. His father had already died and by the end of the year his youngest brother would also be dead; and a combination of romantic and sexual entanglements, along with the difficulty of making the farm work, meant he was planning to emigrate. His delight in living, loving, companionship, ideas, drink and sex was also tempered by a sense of isolation and loss, all of which contributed to spells of depression – his blue devil.

What’s more, this delight was often taken irresponsibly. He fathered 12 children by four women (so far as they can be counted) and was always involved in affairs of one sort or another. He eventually married Jean Armour, but not until she had had two children by him and was pregnant with two more. On the very day of Burns’s burial Jean was giving birth to his final child as well as mothering her existing children and the child of another woman called Anna Park. Burns loved genuinely and intensely; but he did so with little scruple. Even Jean said he should have had two wives.

His proposed emigration was cancelled when his poems were published in 1786. He became the talk of the Scottish literati, and although there was a patronising element in their calling him ‘the ploughman poet’ there was no doubt of his success. It allowed him to undertake a series of tours around the country; he toured with James Johnson who was collecting the songs of Scotland, and who published six volumes of them over the next 16 years. Burns contributed over 150 of these, some in their entirety and some with just the tune – to which he would then add his own lyrics or adapt existing ones. He was born for the role. An upbringing in which he heard folk-tales and -songs made them valuable and familiar; and his gifts as a writer made them new, relevant and immediate again.

Farming was proving unproductive (as well as desperately hard work) and he moved into Dumfries in 1791. He had become an Excise Officer, swearing allegiance to the Crown, and was also involved with the local volunteer brigade. On his deathbed, he asked that ‘the awkward squad should not fire over me’. He seems to have invented the phrase; but it was no use – they fired over his grave anyway. In his last year or so he was desperate for funds, with five children to bring up, and in terrible pain. He died on 21 July 1796 aged 37, the relatively early death blamed on his dissolute behaviour. It is, however, more likely to have been the result of a series of medical conditions arising from rheumatic fever when he was a child, rheumatic heart disease in 1795, bacterial endocarditis, and possibly mercury poisoning. The latter may have been a result of treatment for his liver – so perhaps the dissolute lifestyle had some part to play in the end.

Burns was not a political revolutionary; he did not call people to arms. If anything, he called for them to fall into each other’s (or his). He was not following a series of guiding principles so much as his instincts. But these instincts – for language, humanity, the value of his native culture – were honed by love, friendship, loss, passion, joy and regret. He stated that he wanted to be Scotland’s Bard. He became it. And since his death, he has been appropriated by almost every aspect of Scotland’s culture, even used as a symbol by the Scottish Tourist Board (though it is unlikely that ‘A fig for those by law protected / Liberty’s a glorious feast! / Courts for Cowards were erected, / Churches built to please the Priest’ will ever feature on a tin of petticoat shortbread). These oversimplifications sentimentalise and diminish a man whom Carlyle compared to Homer; whom the Romantics revered; and who wrote with an insight into the heart of people that survives all change.

Notes by Roy McMillan