The NAB Blog

The Prevention of Literature – Censorship and Freedom

By Anthony Anderson

23 March 2023

Earlier this year there was much media coverage surrounding the publication of new editions of books by Roald Dahl. Potentially offensive words had been eliminated or changed… Augustus Gloop was no longer enormously fat, the Oompa Loompas had become gender neutral, while Mrs Twit had ceased to be ugly. Predictably, opinion was sharply divided – some viewing the changes as cultural vandalism, while others seeing them as being sensitive to those ‘with a lived experience of any facet of diversity’.

Earlier this year there was much media coverage surrounding the publication of new editions of books by Roald Dahl. Potentially offensive words had been eliminated or changed… Augustus Gloop was no longer enormously fat, the Oompa Loompas had become gender neutral, while Mrs Twit had ceased to be ugly. Predictably, opinion was sharply divided – some viewing the changes as cultural vandalism, while others seeing them as being sensitive to those ‘with a lived experience of any facet of diversity’.

In this case the textual changes were self-imposed in that they had been made by the Roald Dahl Story Company itself, essentially in response to a society that is ever changing. While most of us would uphold the principle of freedom of speech and ideas, are there any limitations that should be observed – and should these be voluntary (as in this case) or statutory, and, if so, on what principles?

It is almost 400 years since John Milton published his Areopagitica, a criticism of the censorship of books, which prevailed at the time – ‘Who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, God’s image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye.’ His central argument was that it is not for the state to ban ideas and writing – essentially readers should be given a freedom of choice. It is notable that some of Milton’s works were subsequently banned, one of them questioning the principle of divine right. Since then many thousands of books have been banned and destroyed for ideological reasons, often by totalitarian regimes and for reasons that seem abhorrent today.

taking literature out of its historical context is not without the danger that, in adapting texts for modern sensibilities, we lose a large part of the book’s very essence

So while many books have been banned (or amended) on the grounds of cultural sensitivity or politics, a good number of the most notable cases of censorship have been on the grounds of obscenity. Of course, what is considered acceptable is in constant flux. Dr Bowdler’s early 19th-century expurgation from Shakespeare of ‘everything that can raise a blush on the cheek of modesty’, resulted in a loss of almost 10% of the text and nowadays is seen as nothing other than vandalism. In England all plays were required to be approved by the Lord Chamberlain before they could be performed in public – a statute that lasted as recently as 1968. In the mid-16th century, the Roman Catholic Church established the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the definitive list of books that were forbidden to be read by Catholics, which, over the centuries, included titles as innocuous as Robinson Crusoe and Les Misérables.

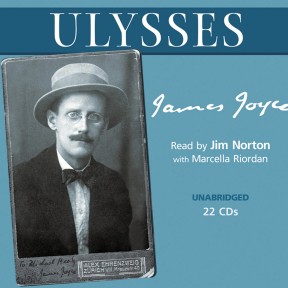

In the 20th century, Ulysses was initially banned in America, an action initiated by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which objected to the chapter we now know as Nausicaa. In 1960, Penguin Books won a notorious obscenity case over Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which the US Post Office had tried to ban a year earlier. The furore over both cases seems ludicrous to us today – tempora mutantur, nos et mutamur in illis.

Given the provenance of much of the material we record at Naxos AudioBooks, this is an issue that we come across fairly often. There are words, ideas and portrayals in many books from past centuries that would be hard to justify if they were published today. Against this is the obligation, and this is one that is important, to present the texts as they were originally written – and this is the prevailing principle we follow in our recordings.

Although many of us alive are fortunate enough to live in an ostensibly free and relatively liberal society, that freedom is not without limits. Cultural sensitivity will continue to be a topic of heated debate for some time to come. However, taking literature out of its historical context is not without the danger that, in adapting texts for modern sensibilities, we lose a large part of the book’s very essence.

« Previous entry • Latest Entry • The NAB Blog Archive • Next entry »