Audio Sample

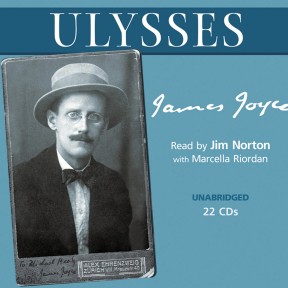

James Joyce

Ulysses

Read by Jim Norton with Marcella Riordan

unabridged

Ulysses is one of the greatest literary works in the English language. In his remarkable tour de force, Joyce catalogues one day – 16 June 1904 – in immense detail as Leopold Bloom wanders through Dublin, talking, observing, musing – and always remembering Molly, his passionate, wayward wife. Set in the shadow of Homer’s Odyssey, internal thoughts – Joyce’s famous stream of consciousness – give physical reality extra colour and perspective. This long-awaited unabridged recording of James Joyce’s Ulysses is released to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of ‘Bloomsday’. Regarded by many as the single most important novel of the twentieth century, the abridged recording by Norton and Riordan released in 1994, the first year of Naxos AudioBooks, is a proven bestseller. Now the two return – having recorded most of Joyce’s other work – in a newly recorded unabridged production directed by Joyce expert Roger Marsh. The recorded text is taken from the 1937 Bodley Head edition.

-

Running Time: 27 h 16 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-597-0 Cat. no.: NAX30912 Download size: 398 MB BISAC: FIC004000 Released: March 2004 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Reviews

One of the crowning glories of audiobooks.

Samuel West, The Times

The most famous ‘yes’ in literature concludes James Joyce’s Ulysses, and it comes after 38 1/2 spellbinding hours in Naxos’s production of this great work. Directed by Roger Marsh, the novel is narrated by Marcella Riordan as Molly and Jim Norton as everyone else. This is, hands down, the best recording of the several versions that exist.

Beyond being the commuter’s friend, the production serves also as a valuable companion to reading the book itself. As local ways of speaking disappear under the global dominion of television, a recording as good as this may become – is already, perhaps – indispensable for recapturing the accents, cadence and intonations of ‘dear dirty Dublin’ on June 16th, 1904.

Both readers are Dubliners, and both seem to have absorbed the book into their beings, their voices restoring the printed words to that speech, inner and outer, which gave rise to so much of the novel. Jim Norton’s ability to render the moods and idiosyncrasies of the countless characters who troop through the pages is close to a miracle. He’s got their way of speaking down in all its versatility and idiosyncrasy, from the lowest tram man shouting destinations at Nelson’s Pillar, to Nosey Flynn snuffling out banalities in Davy Byrne’s pub, to Professor MacHugh at his bloviating oratory, and on and on through aural Dublin. Norton also manages the subtle distinction between outer speech and inner musing, conveying meaning and sense where syntax and even words are absent: ‘Sss, Dth, dth, dth!’ Bloom thinks at one point, and Norton makes it eloquent.

As for Marcella Riordan: Who has not looked upon the dense 50 or so pages of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy without dismay? Who has not struggled to find the long passage’s natural breaks and threads? Riordan’s performance is brilliant. Her voice, free from the slightest histrionic taint, is a little husky and luxuriously sated; and the long passage uncoils, its meaning and feeling burgeoning naturally.

It is impossible to be temperate in praising this production: It is simply the goods.

Katherine A. Powers, The Washington Post

Winner of AudioFile Earphones Award

It is an imposing enough task to attempt a quality unabridged recording of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Add to that the aim to provide the listener with 18 smoothly segued musical transitions consisting of songs and opera excerpts mentioned in the novel; a booklet with a track-by-track commentary, introduction, and explanatory essays; and finally a CD-ROM packed with further supplements (Web links, booklists, interviews with the performers, sound files of Joyce reading excerpts, and more) – and you have as ambitious and rewarding an audio production as any that exists, an audio experience that truly deserves to be cherished. Joyce’s celebrated novel follows Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom as they travel in Dublin on June 16, 1904. Joyce’s inspiration was The Odyssey and the fullness of humanity he recognized in Odysseus, whose adventures he obliquely recreates in the wanderings of Bloom. Following along with the novel while listening to the discs reveals the enormous care that director Roger Marsh and reader Jim Norton lavish on the project. Their orchestrated performance is a work of love and respect for Joyce and his experimental, poetic, funny, musical epic book. Jim Norton has a wonderfully rich and friendly voice, appreciative of the humor and cadences of the text and even of the onomatopoetic textual noises of cat purrs, door creaks, and print-press groans: ‘Everything speaks in its own way.’ His performance turns a challenging book into an inviting, even a hypnotic, one. Marcella Riordan satisfyingly performs the dialogue of Molly Bloom, including the 24,000-word unpunctuated stream-of-consciousness passage that concludes the novel. Readers of Ulysses have long been encouraged to read out loud the more difficult sections for added comprehension and enjoyment of the language. Now, thanks to Naxos, the entire book is available in a performance to savor. It is safe to say that anyone wanting to experience the preeminent work of modern fiction has in this package the perfect audio companion.

G.H., AudioFile

Booklet Notes

Ulysses is one of the greatest literary works in the English language. It created a stir as soon as it was published in 1922, partly because of the experimental nature of the writing and formal design and partly because in certain passages it contained more than usually explicit language. Indeed, the book was banned in this country until 1936, and a New York court required expert witnesses to testify to its artistic merit. Despite such auspicious notoriety, Ulysses has remained more famous than popular, and for one simple reason: it is a very difficult book to read. Not as difficult as Joyce’s final novel, Finnegans Wake, to be sure, but difficult nevertheless. The proof of its greatness, however, is that it rewards effort with an endless feast of delights, the more delightful for being hard won.

Different trains of thought constantly intercut one another

Put simply, Ulysses is an account of a single day in Dublin, June 16th 1904, seen from the perspective of three characters: Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom and Bloom’s wife, Molly. Readers of Joyce’s earlier novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, will recall Stephen Dedalus as its central character – Joyce’s own alter ego. Indeed, the confusion of fact with fiction continues in Ulysses. Virtually all the characters, from Bloom himself to the dozens of Dubliners with whom he collides during the course of the day, are based in some way on real people known to Joyce, just as all the references to the streets and buildings of Dublin are factually correct in every detail.

Leopold Bloom, an advertising canvasser, is the real protagonist of this novel. He is Ulysses. ‘Ulysses’ was the Roman name for Odysseus, and this novel is, in one way, an updated version of Homer’s epic tale: the Odyssey. In Homer, Odysseus wanders for several years over several seas, before returning home at last to his faithful wife Penelope. In Joyce’s novel, Bloom wanders for but a day through the streets of Dublin, before returning at last to his faithless wife Molly. In Homer, Odysseus escapes from the cave of the one-eyed Cyclops, the Cyclops hurling rocks after his ship as he sails away. In Joyce, a drunken Irish nationalist, blinded by the sun in his eye, hurls a biscuit tin after Bloom (Jewish, and therefore a foreigner) as he makes his escape on a jaunting car. This is one of the many hundreds of clever parallels with the Odyssey, most of them so subtle that they go unnoticed.

Musical references abound too. At the start of Bloom’s day he takes breakfast in to Molly, still in bed, along with the morning post. This includes a card from the impresario Hugh ‘Blazes’ Boylan, informing Molly of the programme she is to sing in a forthcoming concert tour which he is arranging for her. On the programme are the seduction duet Là ci darem from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and the popular Love’s Old Sweet Song. Boylan is to call that afternoon to go through these with her – though in point of fact he and Molly have rather more than musical rehearsal in mind. Bloom is well aware of all this, and for this reason Là ci darem and Love’s Old Sweet Song are very much in his thoughts throughout the day. In the final chapter, too – Molly’s famous ‘stream of consciousness’ monologue – snatches of the two numbers rise constantly to the surface, both consciously (as she imagines how she will perform them) and unconsciously (to accompany her careful breaking of wind).

The ‘stream of consciousness’ technique, for which the novel is so famous, is one of the things which makes it so hard to read. Different trains of thought constantly intercut one another (as they do in real life), often without helpful punctuation, often leaving ideas or even words incomplete, and often making it hard to separate reality from fantasy, trivial matters from matters of significance. This last problem is particularly tricky, for in Joyce apparently trivial events or remarks can suddenly assume a huge significance.

An example: when Bloom is pestered by Bantam Lyons, who wants to borrow his newspaper to check on the horses running in the Gold Cup later that day, Bloom tells him to keep the paper, as he was only planning to throw it away. By coincidence (and unbeknown to Bloom), there is a horse called ‘Throwaway’ running in the race, with odds of twenty to one. Bantam Lyons takes Bloom’s remark to be a tip and hurries off excitedly. Much later, when Throwaway actually wins the race, there is huge resentment among the assembled company at Kiernan’s pub that Bloom had kept this tip to himself, and it is this which leads to the argument that ends with the biscuit tin episode.

Even more unusual, perhaps, than the stream of consciousness passages, is the chapter describing Bloom and Stephen’s adventures in ‘Nighttown’ – the brothel area of Dublin – in the early hours of the morning. This chapter, the longest in the book, is set out like a play script, with capitalised character names, followed by stage directions and lines spoken by that character. Although an important episode in the narrative, it also becomes a wild phantasmagorical fantasy, with lines given to the gasjet and the fan, as well as brief appearances by Lord Tennyson and King Edward the Seventh. The whoremistress Bella Cohen appears in male apparel and is referred to as ‘Bello’ as she booms out her orders to Bloom (now female) and whips and threatens him. Bloom has come to the brothel to keep an eye on young Stephen Dedalus, who is far too drunk for his own good. When Stephen wildly smashes a gas lamp and races out of the house, Bloom follows after him and eventually takes him home to his own house to sober him up.

The chapter that follows takes yet another unusual literary form – that of question and answer. Here, answers given to direct questions about the sequence of events as they unfold are often elaborate, even pedantic, and usually very amusing, with no detail going unremarked. At the end of the chapter, Bloom, now finally home in bed with Molly (they sleep head to toe, however), drifts off to sleep with two last questions:

When?

Going to a dark bed there was a square round Sinbad the Sailor roc’s auk’s egg in the night of the bed of all the auks of the rocs of Darkinbad the Brightdayler.

Where?

Yes because he never did a thing like that before as ask to get his breakfast in bed with a couple of eggs…

The final chapter, Molly’s interior monologue, begins with a marvelous and subtle joke. Listening to her husband’s final sleepy murmurings, she has taken them to be a request for morning room service.

Ulysses abounds with jokes such as this; for, long and difficult as it is, it is in fact a comic novel. For the reader many of the jokes have to be dug out, worked out through careful study – but for the listener many of the barriers to understanding simply disappear. Brought to life through the spoken word, the difficulties melt away, to leave a narrative as natural, as amusing and as moving as anything you have ever read.

Roger Marsh