The NAB Blog

Intimate Letters: The Epistolary Novel

By Anthony Anderson

27 October 2018

The art of letter writing may seem unfashionable in a world dominated by tweets and posts. However, the practice goes back almost as far as the history of writing itself, and, as well as letter from one person to another, also expanded as a form to include letters written to be read by a wider public – witness, letters written to newspapers in our own time. In this vein, ‘open’ letters have often been used for political ends – Zola’s J’accuse perhaps being the most notable example.

However, it is letters which were intended to be kept private that give a sense of intimacy and insight. For example, Oscar Wilde’s letter to Lord Alfred Douglas, De Profundis, or Virginia Woolf’s suicide note to her husband, Leonard. For us to be able to read these today seems a little intrusive, but they can give us a deepened understanding of writers as human beings.

In fiction, letters (and diary entries) have been frequently deployed as the fabric with which a story is told – ever since Aphra Behn’s Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister in 1684. In the mid 18th century the form was very popular, with writers such as Tobias Smollett and Fanny Burney making use of the device. In our own time there are numerous novels which do the same – The Color Purple, We Need to Talk About Kevin and The White Tiger.

The story skilfully unfolds through the novel’s forty characters and 789 letters

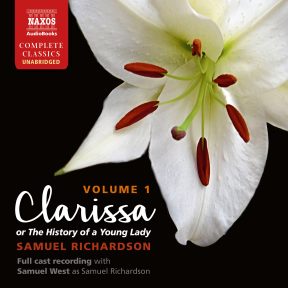

That this intimate form has been used as the basis of many works of fiction is no surprise as the letter writer’s ‘voice’ gives us a very different and, apparently, more honest perspective than that of a first person (and more neutral) narrator. One of the earlier epistolary novels in the literary canon is Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, but it is his masterpiece Clarissa which stands out as a giant of the genre (it is regarded as one of the longest novels in the English language – which presented us with something of a logistical challenge when it came to recording this magnum opus). In its complexity, Richardson developed the epistolary form. Samuel Johnson described Clarissa as ‘the first book in the world for the knowledge it displays of the human heart.’

Clarissa Harlowe is a tragic heroine (Richardson decreed her a cruel fate indeed – much to the dismay of many readers since the book’s publication in 1748). In order to avoid a loveless marriage planned by her family she finds herself in the power of libertine Robert Lovelace, with disastrous consequences – a fatal attraction indeed. The story skilfully unfolds through the novel’s forty characters and 789 letters. In our recording the title is deftly voiced by Lucy Scott, who lends the character a virtuous innocence, although, unlike the case of Richardson’s other famous heroine Pamela Andrews, virtue is certainly not rewarded.

On its publication, Clarissa rapidly became cult reading among English readers. Interestingly, this History of a Young Lady was quickly followed a year later by the publication of Tom Jones by Henry Fielding. Together these books marked a significant advance in literary history, laying the foundation for the modern novel.

But we return to Dr Johnson for the final verdict on Clarissa. He is said to have famously advised: ‘Why, sir, if you were to read Richardson for the story… you would hang yourself… you must read him for the sentiment.’

« Previous entry • Latest Entry • The NAB Blog Archive • Next entry »