Audio Sample

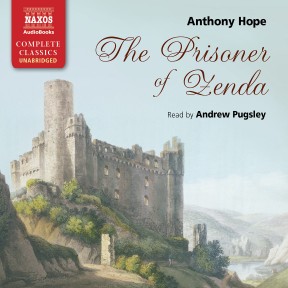

Anthony Hope

The Prisoner of Zenda

Read by Andrew Pugsley

unabridged

The ultimate escapist adventure story, The Prisoner of Zenda transports the listener into a bygone era, awash with swashbuckling heroism, cunning plots and courtly love. The popularity of Hope’s tale of intrigue was such that it spawned an entirely new genre known as the ‘Ruritanian romance’. When the King of Ruritania is kidnapped, the onus falls on a British tourist, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the King, to stand in for him and to avert disaster by coming to his rescue. The frequent replays of the film with Ronald Colman and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. testify to the continuing popularity of this evergreen adventure. Andrew Pugsley’s reading captures the excitement and the momentum.

-

Running Time: 5 h 28 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-939-8 Cat. no.: NA513512 Download size: 80 MB BISAC: FIC004000 Released: June 2010 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Reviews

Anthony Hope created the mould for the ripping adventure yarns of the early 20th century. Andrew Pugsley gives a spirited reading of the hugely popular Prisoner of Zenda, in which Rassendyll stands in for his kidnapped cousin, the rightful King of Ruritania, falls in love with Queen Flavia, defeats the dastardly Rupert of Hentzau, frees the king and nobly abjures his love.

Christina Hardyment, The Times

Booklet Notes

Anthony Hope Hawkins was, like his hero Rudolph Rassendyll in The Prisoner of Zenda, the epitome of the English gentleman. He had an exemplary education: Marlborough public school, then Balliol College, Oxford, where he achieved a first-class degree and was President of the Union. In 1887 he took silk, and became a barrister. Under the pen-name of Anthony Hope he had begun to write short stories and novels, which met with little popular success. He nevertheless felt drawn to the literary world, even though writing fiction conflicted with his legal work. And then, in 1893, as he recalled in his autobiography: ‘I was walking back from Westminster County Court, when the idea of Ruritania came into my head.’

The Prisoner of Zenda, the result of Hope’s idea of Ruritania, was a hugely successful novel, and it gave the English language a new adjective: ‘Ruritanian’. Published in 1894, it went into several editions, was turned into a stage play, and has also been filmed several times, firstly in the silent era in 1913 and then in 1922, with Ramon Navarro. The classic version is perhaps that of 1937, which starred Ronald Colman, followed closely by the 1952 version with Stewart Granger, Deborah Kerr and James Mason. In 1979 Peter Sellers appeared in a knockabout satirical version.

The book has as its hero the red-haired Rudolph Rassendyll, a minor English aristocrat who, through a common ancestor in the 18th century, bears an uncanny resemblance to Rudolph Elphberg, who is about to be crowned King of Ruritania. Travelling to Ruritania out of curiosity to see the coronation, Rassendyll becomes enmeshed in court and political intrigue when the future King’s younger brother, ‘Black’ Michael, attempts to usurp the throne. Michael’s plan is to drug his brother and so delay the coronation, but he is foiled by the King’s faithful officers, Colonel Sapt and Von Tarlenheim, who persuade Rassendyll to take advantage of his close likeness to the future King and impersonate him at the coronation. Their plan is successful until Michael finds the real King in hiding, and imprisons him in the dungeon at Zenda castle. Rassendyll, while still pretending to be the King, works on a plan to release the rightful monarch. The situation is further complicated when Rassendyll falls in love with the King’s intended bride, Princess Flavia, who is unaware of the impersonation. The subsequent adventures, and the sense of ironic playfulness throughout, have been models for many similar adventures in other novels, and a score of swashbuckling film scripts.

There is no doubt

that Hope wanted

to create a hero

who would be a

role-model for the

England of 1894

The Prisoner of Zenda is a classic novel in the new ‘romantic’ genre that was so popular at the end of the 19th century. Hope said of this genre: ‘From romance we gain fresh courage, fresh aspiration, fresh confidence in the power of the human spirit and in the unconquered confidence of the human mind.’ Less academically, he also stated that those who enjoyed romantic fiction ‘dream, and are none the worse for their dreams’.

It is interesting to consider why a taste developed in the late 19th century for tales set in imaginary, fanciful kingdoms somewhere in Europe, where monarchs are under threat from rival usurpers, and a hero aids the struggle for the rightful monarch to prevail. Ruritania was one of many such. Hope created another, Kravonia, in a later novel, Sophy of Kravonia (1906); Dracula’s Transylvania might also be included in this list.

In the Europe of 1894 the political balance showed signs of change. England was experiencing social unrest and a growth of radicalism. There was political uncertainty in Bulgaria and Hungary. In Russia Tsar Nicolas II, a weak man manipulated by the monk Rasputin, ascended the throne. Nicolas would be the last Tsar, his poor government leading to the Russian revolution – a sequence of events that might itself be the outline of a plot for a Ruritanian adventure! The French President was assassinated by an Italian anarchist, and the infamous Dreyfus case uncovered corruption in the French government at the highest level. Concern also grew about the territorial ambitions of the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II. It is no wonder that escapist literature such as The Prisoner of Zenda proved to be so popular.

The indolent Englishman Rudolph Rassendyll spawned other fictional heroes who, without a sense of purpose, find their true role in life only through action for a cause; examples are Richard Hannay in John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps or Bulldog Drummond in Herman McNeile’s eponymous novel. Hope instils the feudal ideas of loyalty, allegiance and even courtly love into the modern Englishman, Rassendyll, by placing him in a fantasy land in which time seems to have stood still, in which such medieval virtues are still pertinent. Rassendyll returns to late-19th-century England with these virtues that ought to belong to every Victorian gentleman still intact and indeed reinforced, ready to be utilised in the modern world. His moral rectitude, particularly in his treatment of Princess Flavia, is an example of behaviour found lacking in the true King (who did not have the advantage of an English education). There is no doubt that Hope wanted to create a hero who would be a role-model for the England of 1894. Rassendyll is not without vulnerability, however. The flashy and reckless Rupert of Hentzau, almost Rassendyll’s equal in class and intelligence yet on the other side in the conspiracy, sows the seed of dishonour in Rassendyll’s mind regarding the ultra-feminine Princess Flavia. Should he follow Love or Honour? It provides a few tricky moments of indecision on our hero’s part. Honour of course prevails.

In response to the success of The Prisoner of Zenda Hope gave up the law to be a full-time writer. His dashing character Rupert of Hentzau gave his name to a swashbuckling sequel in 1898, but Hope never quite achieved again the same popular triumph. (In another vein entirely was his The Dolly Dialogues, also published in 1894; this satire on late-Victorian society manners, witty and flirtatious in tone, can still charm today.) In 1914, with the outbreak of war, Hope was drafted in to assist the English government in their efforts to counter German propaganda. His literary skills, as exemplified in The Prisoner of Zenda, were so effective that he received a knighthood for his services in 1918.

Hope was modest about the achievement of his famous novel: ‘The root idea is of course merely a variation on an old and widespread theme of mistaken identity … I think that two variations which struck the popular fancy in my little book were royalty and red hair.’

Notes by David Timson