Audio Sample

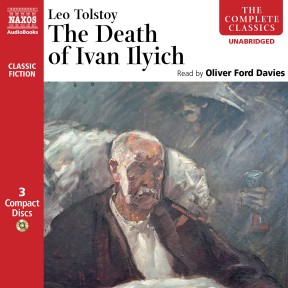

Leo Tolstoy

The Death of Ivan Ilyich

Read by Oliver Ford Davies

unabridged

Drawing on the experience of his own struggle to find enlightenment and a deeper spiritual understanding of life, Tolstoy in The Death of Ivan Ilyich takes us on the final journey towards death with Ivan Ilyich, who, falling victim to an incurable illness, ponders on his own life – its shallowness and lack of compassion, wondering what is the meaning of it all. At times sombre, at times satirical, Tolstoy’s novel raises questions about the way we live and how we should strive even at the end to seek final redemption. It is a powerful masterpiece of psychological exploration, and has influenced writers as diverse as Hemingway and Nabokov.

-

Running Time: 2 h 51 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-570-3 Cat. no.: NA385112 Download size: 42 MB Translated by: Aylmer and Louise Maude BISAC: FIC004000 Released: November 2007 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Reviews

Tolstoy wrote his short novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich after a dark night of the soul that led him to question his entire life, and eventually to find comfort in Christianity and peasant simplicities. The book is a coded version of his suffering and makes tough, but ultimately deeply rewarding listening. Oliver Ford Davies, the philosopher and actor fresh from a memorably gruff rendering of Diogenes Laertius for the Naxos audiobook Ancient Greek Philosophy, makes the dying Ilyich touchingly human.

Christina Hardyment, The Times

Painfully and slowly, Judge Ivan Ilyich is dying and, as he does so, he comes to recognise the truth about his impeccable life. For all his propriety and success, it has been meaningless and empty. Ilyich loathes his wife and realises his ‘concerned’ colleagues are merely waiting to step into his shoes. And he recognises the selfless devotion with which he is cared for by the peasant boy Gerasim as the only real truth in the whole of his own shallow life. Only at the end, when Ilyich breaks through the ‘black sack’ of death, is he absolved. Ford Davies’s leisurely narration and the passages of Russian music complement Tolstoy’s serious theme and his presentation of Ilyich’s anguished emotions is masterly.

Rachel Redford, The Observer

Enough of these homegrown comedies of manners. There aren’t many jokes in this relentless novella about a cold, calculating, materialistic minor member of the St Petersburg judiciary, whose only ambition is to keep up with the Ivanovs. Until, that is, he falls ill with a mysterious terminal disease that opens his eyes to the shallowness of his friends, his family and, most of all, himself. Tolstoy’s prose is majestic, his pace measured, his characters unflinchingly true to life, his message bleak. If you’ve never read any Tolstoy, best not start with this one – you might top yourself before you get round to Anna Karenina.

Sue Arnold, The Guardian, 16 February 2008

In the lovely, low tones of a fine storyteller, Oliver Fox Davies guides us through the stages of Tolstoy’s mini masterpiece. Davies’s skill with inflection, even within words, heightens the social satire of the early section and shifts with Ilyich’s slide into ever increasing pain and irritability. With the terror and anguish of approaching death, his voice grows convincingly hoarse. Until his illness, Ivan Ilyich had never reflected on his life. But he slowly comes to see his life as ‘a terrible, huge deception which had hidden life and death.’ As he lays dying, his lifelong friends think of the promotions that may come their way, and his wife ‘began to wish he would die, but she didn’t want him to die because then his salary would cease.’ He has always avoided human connection, but through the tender ministrations of a peasant he comes to recognize the ‘mesh of falsity’ in which he’s lived. Written more than a century ago, Tolstoy’s work still retains the power of a contemporary novel.

Publisher’s Weekly, January 2008

Tolstoy’s novella offers a penetrating examination of the Christian faith and the nature of life and death. Listeners will also be sure to delight in Tolstoy’s sharp and sometimes satirical eye for the very modern-sounding details of the life of a nineteenth-century Russian bureaucrat. With masterful ease, a warm tone, and conversational pacing, British actor Oliver Davies captures Ivan Ilyich’s preoccupation with interior decorating and debt and his avoidance of family weddings and home remedies. Then the shadow of death wipes away all trivialities and pretence. This work’s prose and performance are so vivid, so human, and so listenable that there’s no doubt why Tolstoy stands as one of the giants of world literature.

B. P., AudioFile Magazine

Booklet Notes

The Death of Ivan Ilyich was written at a time of great crisis in Tolstoy’s life. He was questioning his faith – the Orthodox Christian religion in which he had been brought up. He wanted to face up to the inevitability of death and make some sense of it. The result was The Death of Ivan Ilyich, in which he follows the gradual process of a man wasting away through death, and in the process discovering the truth about himself, his family and friends. He recognises the lives they all lead are shallow, self-centred and ultimately worthless, though he had always believed he was leading a good and moral life, but as the mercilessly objective narrator of the story says:

‘Ivan Ilyich’s life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible.’

Ivan had never reflected on his life until the moment of his death. The simple goodness of the peasant boy Gerasim, who attends him in his final illness, tells Ivan more about the true purpose of life than his wife or any of his close friends can communicate. In a Christ-like compassionate way, Gerasim serves and helps the dying Ivan without complaint or self-interest, accepting that death is a part of nature, and Ivan enjoys being comforted and cared for like a little child. It is the human contact he has denied himself for so long. Gradually Ivan realises this is the ‘real thing’ and he’s been living a false life obsessed with materialism, never examining or questioning its true value. In his final illness he now sees his own worthlessness reflected in the lives and attitudes of those around him. He sees his wife contriving to blame him for the inconvenience he is causing her; his daughter Lisa, bored with his illness that interrupts her social life; his friends and colleagues in the judiciary totting up the opportunities that will be created by his death. They do not, or will not, or are afraid to connect with Ivan’s suffering. Self-preservation comes first, and as the death drags on through the weeks, their apathy towards Ivan grows, just as Ivan’s hatred for them as representatives of his own shallow life proportionately increases.

‘How it happened it is impossible to say because it came about step by step, unnoticed, but in the third month of Ivan Iych’s illness, his wife, his daughter, his son, his acquaintances, the doctors, the servants, and above all he himself, were aware that the whole interest he had for other people was whether he would soon vacate his place, and at last release the living from the discomfort caused by his presence and be himself released from his sufferings.’ (Chapter 7)

Ivan’s struggle with death mirrors Tolstoy’s own life-long struggle, both spiritual and intellectual.

Born into the Russian nobility, most of his fellow countrymen would have envied him, he was wealthy and well-educated, married at 34 and had 13 children. Secure and prosperous, it was in these years Tolstoy wrote War and Peace and Anna Karenina. But he was not comfortable as a wealthy landowner, who owned many serfs, whose poverty and ignorance played on his conscience. Just as Ivan began to recognise in the peasant Gerasim the real meaning of life, so Tolstoy too reflected on the value of a peasant’s life: its peace and simplicity, as he saw it, came from a complete faith in God. These feelings came to a head in 1876, and for nine years Tolstoy gave up fiction writing to explore in depth his own spirituality, or lack of it. He wrote the autobiographical A Confession in 1882, in which he declared that he suffered from depression because he could find no meaning in life, and developed his thoughts further in tracts with titles like The Kingdom of God is within you.

Over a ten year search Tolstoy evolved his own brand of Christianity focusing on Christ as a model of love in action, and a belief in non-resistance to evil. The struggles, dilemmas and agonies Tolstoy went through during this period resulted in the minor masterpiece: The Death of Ivan Ilyich, in which he uncompromisingly draws on his own experiences and contemplations on the painful process of death. A process involving self-examination that Tolstoy sees as necessary to find true peace and happiness.

As he nears his end, Ivan in his stupefied state feels that ‘he and his pain were being thrust into a narrow, deep black sack, but though they were pushed further and further in they could not be pushed to the bottom…he was frightened yet wanted to fall through the sack, he struggled but yet co-operated. And suddenly he broke through, fell, and regained consciousness… (Chapter 9)

A symbolic journey where he is ‘born again’, and only after which he can see clearly for the first time the mistakes of his life, a life ‘trivial and often nasty’, and the possibility of God’s forgiveness. Only after his intense suffering is he aware that he is spiritually empty and what he thought was the ‘right’ way to live was merely pandering to the petty and meaningless rules of a shallow society. Even at his last breath, he realises that if he can overcome his hatred for his wife and family and show them genuine compassion it will bring him peace in death:

‘He was sorry for them, he must act so as not to hurt them: release them and free himself from these sufferings. ‘How good and how simple!’ he thought. (Chapter 12)

Understanding and compassion bring him release from pain and the incessant question ‘Why?’ that has troubled him since his illness took hold. The genuine grief of his son acts as a catalyst, and it seems that this one moment of penitence makes up for his entire mis-spent life. The Christian values, so important to Tolstoy, are here self-evident.

As Ivan approaches his inevitable death, the mood of the novel darkens and becomes increasingly sombre and terrifying, but the early part is lighter, and satirical in tone.

The story opens with events after the death of Ivan, where the hypocrisy of his family and friends is expressed in almost farcical terms. As Ivan’s wife, Praskovya Fedorovna talks to his friend Piotr Ivanovitch about her husband her shawl gets caught on a piece of furniture, and he tries to remain attentive whilst attempting to sit quietly on a noisy pouffe. Keeping up appearances seems to matter more to these people than compassion. Likewise, the account of Ivan’s early life revealing his growing obsession with materialism, is treated lightly. The pernickety concern for the furnishings in his new home call to mind the snobbery of Mr.Pooter, the eponymous hero of The Diary of a Nobody.

‘Sometimes he even had moments of absent-mindedness during the court sessions and would consider whether he should have straight or curved cornices for his curtains. He was so interested in it all that he often did things himself, rearranging the furniture, or rehanging the curtains.’ (Chapter 3)

This obsession with the trivialities of life is shown to be literally responsible for his downfall, to be redeemed only at his last breath.

One of the powerful images of approaching death Tolstoy employs in The Death of Ivan Ilyich is the feeling of being in a railway carriage ‘when one thinks one is going backwards while one is really going forwards and suddenly becomes aware of the real direction.’ Tolstoy met his own death in 1910 at the age of 82. He died on a cot in a remote railway station.

David Timson