Audio Sample

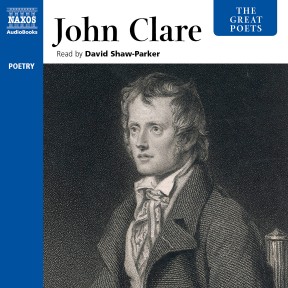

John Clare

The Great Poets – John Clare

Read by David Shaw-Parker

unabridged

John Clare was the forgotten Romantic poet, until the late twentieth century. Known by his contemporaries as the ‘Peasant Poet’ he recorded in his poems the natural landscape of rural England before the Industrial Revolution. His poems rival Wordsworth’s for their sensitivity to nature and pantheism: ‘I feel a beautiful providence ever about me,’ Clare wrote. But his life was a long struggle against poverty and mental collapse. Some of his finest poems were written in the local asylum.

-

Running Time: 1 h 01 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-1-84379-603-9 Cat. no.: NA0094 Download size: 15 MB BISAC: POE000000 Released: August 2013 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

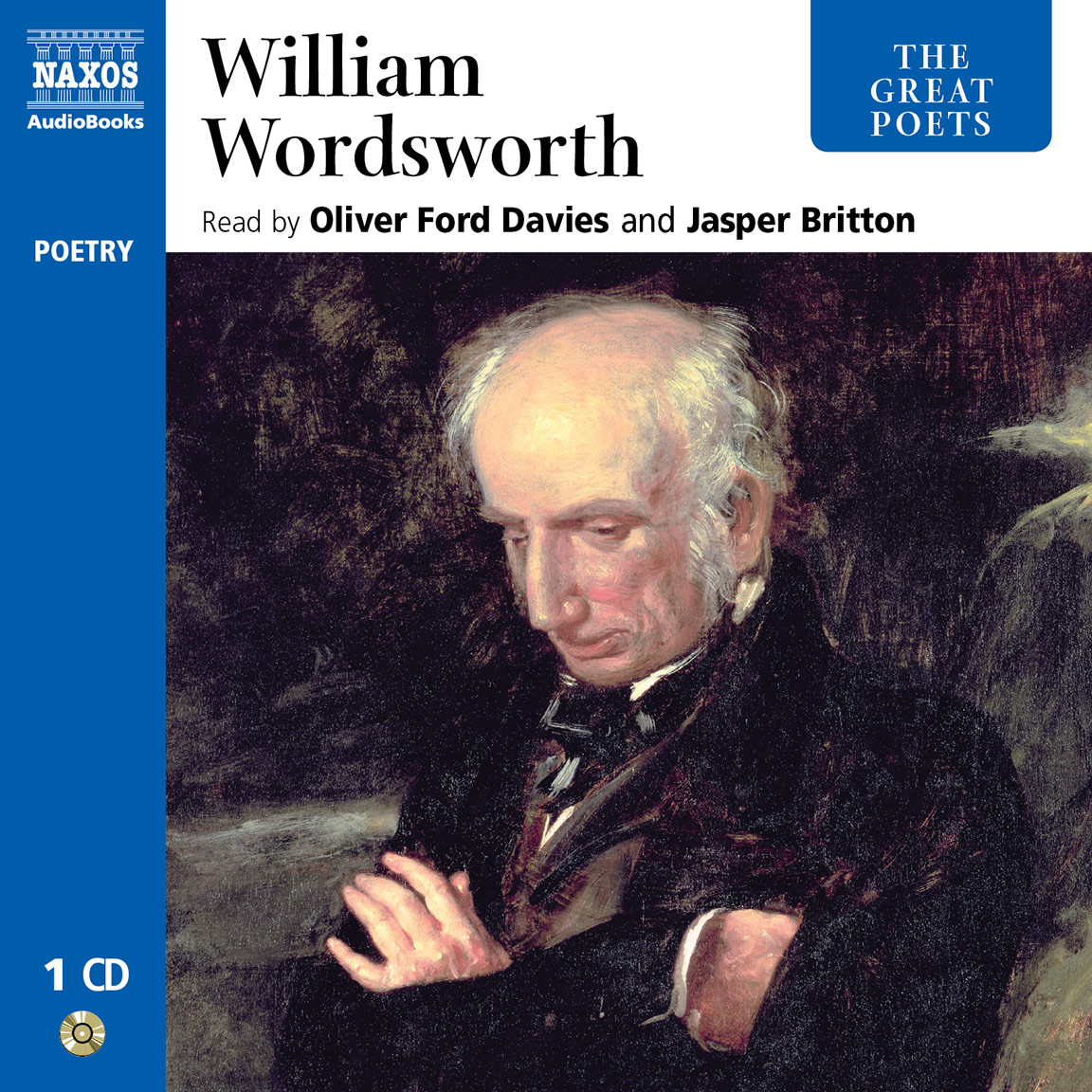

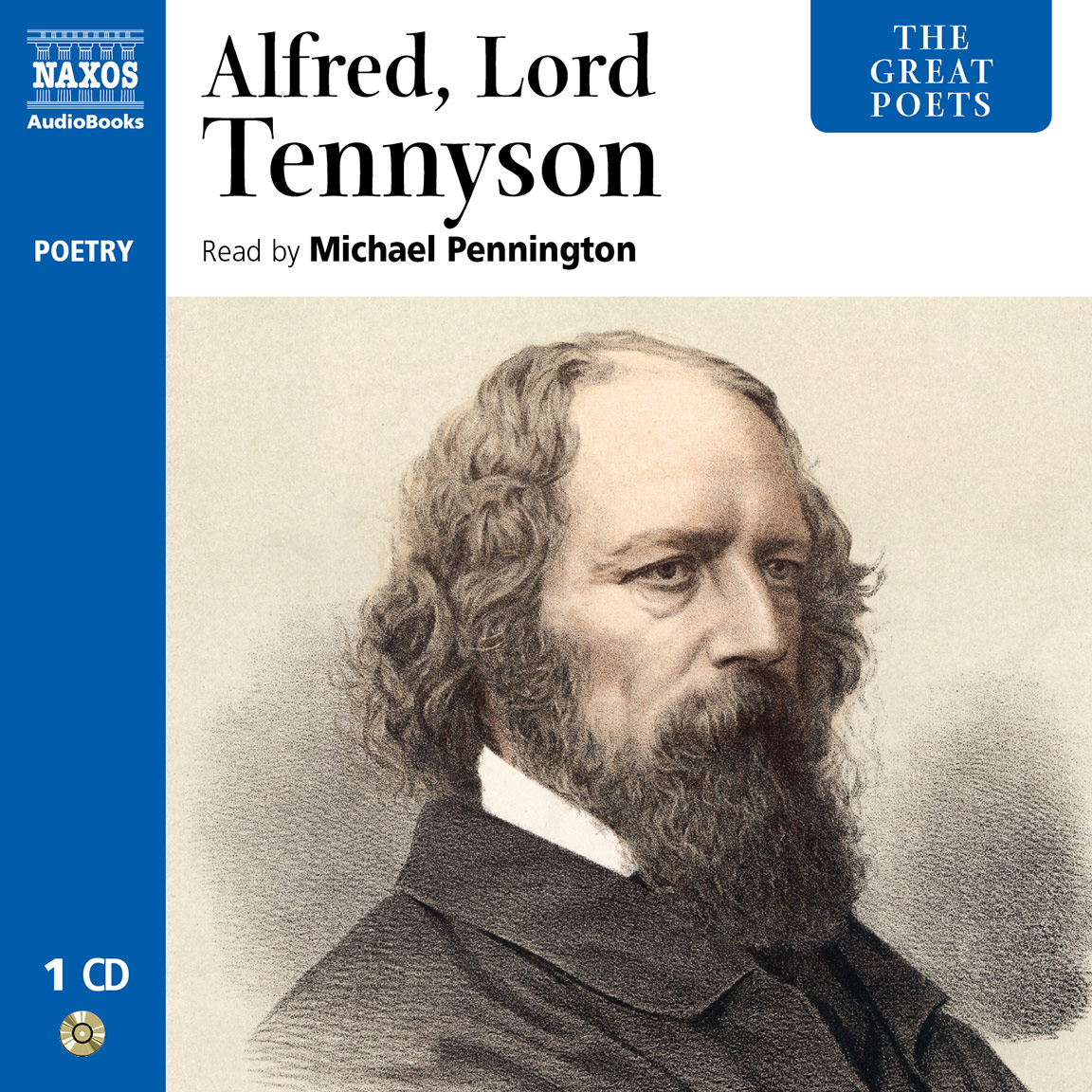

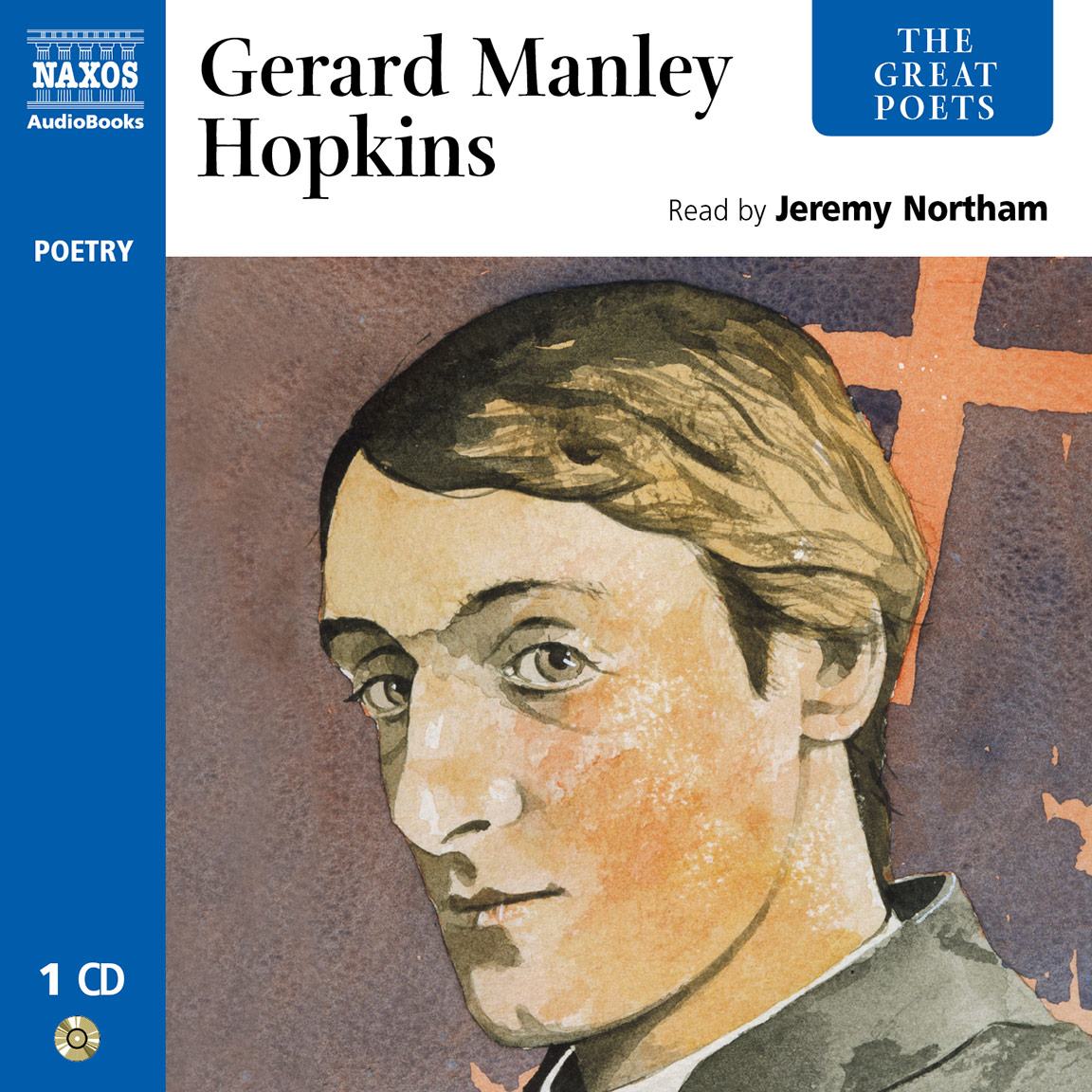

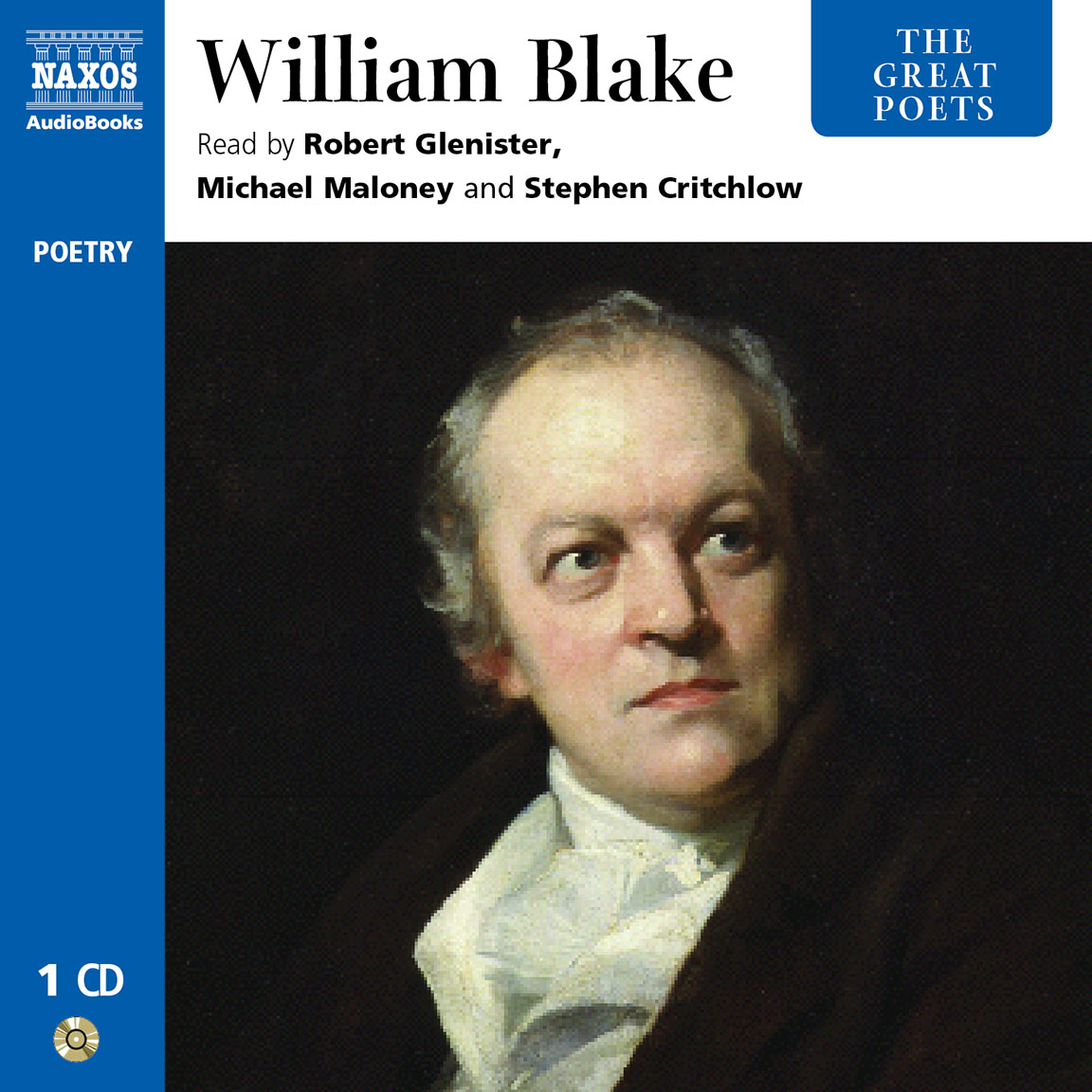

You May Also Enjoy

Included in this title

- To John Clare

- Morning

- The Robin’s Nest

- The Cuckoo

- Summer

- Insects

- The Skylark

- In Hilly-Wood

- The Nightingale’s Nest

- First Love

- Song’s Eternity

- Remembrances

- Summer Evening

- Badger

- To a Fallen Elm

- Love and Solitude

- Autumn Birds

- November

- The Flood

- Farewell

- What Is Life?

- I Am

- Christmas

- The Peasant Poet

Reviews

Even many people who know poetry aren’t familiar with John Clare. Why listen to this reading of some of his work, then? ‘The Peasant Poet’, as he was known, fit in with his contemporaries, the Romantics, but, unlike them, his knowledge of nature was from working in it, not strolling in it. Narrator David Shaw-Parker takes advantage of the poetry’s strong structural elements and uses emphasis to aid interpretation. He also varies his voice to match the tone of each poem – from the pure rustic to the elevated, almost erudite, tone Clare sometimes achieved despite his almost total lack of formal education. This is a fine introduction to Clare’s work.

D.M.H., AudioFile

Booklet Notes

John Clare considered himself largely to be a failure as a poet, which no doubt contributed to his mental illness during which he described himself in the poem I am as ‘the self-consumer of my woes’ whom ‘friends forsake… like a memory lost’. And his subsequent reputation, until the late twentieth century, has been that of the forgotten nature poet – the ‘Peasant Poet’ – and one of the minor romantic poets. Yet as a young man of 27, Clare had achieved fame with his very first volume of poems, Poems descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, and there was a flurry of interest from aristocrats and the gentry who came to rural Northamptonshire to see the ‘Peasant Poet’ in person, and wonder at his natural, untaught poetic gifts.

But Clare was no natural poet warbling ‘his native woodnotes wild’, as John Milton liked to think Shakespeare was.

True, Clare was born, on 13 July 1793, into peasant stock; his father was a labourer in the fields, and illegitimate, and his mother was illiterate, with a superstitious fear of books. His birthplace Helpstone was in Northamptonshire, then as now one of England’s most rural counties. Clare’s rudimentary education was frequently interrupted by his father’s poor health which meant he couldn’t afford to pay school fees for his son. However, Clare developed an obsession with learning, which resulted in his poems being more consciously constructed than his contemporaries realised, though he always hated grammar, considering it a ‘tyranny’ over free expression, and his poems are therefore full of eccentric punctuation, idiosyncratic spellings and dialect words.

Clare’s

own poems

challenge

Wordsworth’s

for their

sensitivity

to nature and

pantheism

Complementing Clare’s learning was a passion for walking through the fields and woodlands around his village, where he first felt the empathy with nature that he began to express in poetry. The early poems were influenced by the style of James Thomson’s The Seasons, one of Clare’s treasured collection of books. As a gardener, and later a ploughboy, Clare had the opportunity to work with nature and learn at first-hand about the seasonal cycles of the English countryside, observing and recording the minutiae of natural life. For example, in Insects Clare describes their miniature world with the precision of a microscope, and in others, he sits with scrupulous patience waiting for the nightingale to emerge, or the robin, or the many other birds whose calls and habits he knew intimately. His poems are a picture of Northamptonshire and the Fens just as Wordsworth’s are of the Lakes. Clare paints in words the broad sweep of the Fenland to the east of the Midlands, the animals and plants that are native to the area and the day-to-day activities of the people who live there, particularly the children. He has left us a detailed account in verse and his other writings of pre-Industrialised England.

In 1809, Clare’s idyllic world of nature received a body blow when Parliament agreed to enclose large sections of England’s common land. For centuries, acres of common land had been fully available for poor peasants to graze their animals on, and open to anyone to walk over as they wished. With the legislation, vast areas of the English countryside were privatised and enclosed within hedges as private fields; old ways were barred by fences and gates. It caused a bitterness in Clare’s heart that found expression in poems like Remembrances or To a Fallen Elm, where the devastating change to the environment is laid firmly at Man’s door, sounding a contemporary note to our twenty-first-century ears: ‘Enclosure like a Buonaparte let not a thing remain, / It levelled every bush and tree and levelled every hill / And hung the moles for traitors…’ (To a Fallen Elm).

Clare’s simple communion with nature made him a solitary, unsociable man, who found it difficult to make friends. Yet he managed to lead a complicated love-life. He seems to have felt obliged to marry Martha (Patty) Turner because she fell pregnant, but in fact he loved his children, and eventually had six. However, he never forgot his first love, Mary Joyce – their courtship had been put a stop to by her father. The poem First Love expresses, perhaps, an idealised memory of her and the many other liaisons he had.

In 1819 a local bookseller in Stamford recognised Clare’s talent and recommended him to his cousin John Taylor, a publisher in London, who already had a growing reputation as a publisher of romantic poets, having printed Keats’s Endymion the previous year.

The publishing of his poems brought Clare fame, but very little financial reward, although it did enable him to get married and prevent his parents in their destitution from having to go to the workhouse. When all too soon the money had gone, he at first existed on support from the gentry, but then was forced to return to working on the land. Although he courted his new-found fame he felt depressed, vulnerable and alienated amongst his new middle-class admirers.

Subsequent collections of poems, however, never matched his first volume in sales. When trying to release some capital from Taylor, in anticipation of sales, he was told not to ‘be ambitious but remain in the state in which God had placed him’. The publisher no doubt felt any potential success of the Peasant Poet would be frustrated if he moved out of his class.

The rest of Clare’s life consisted of the uneasy balance between his prolific output, the facility for writing verse came easily to him, and his, at times, desperate search for financial support. The strain on his weak nervous system became too much, and in 1837, after seeming not to recognise his wife or children, Patty, at his publisher’s suggestion, committed him to a private asylum in Epping Forest. Four years later he escaped and walked the hundred miles back to Northamptonshire. His wife vowed to ‘try him for a while’, but his delusion that he was married to Mary, his lost first love who was long dead, forced her to commit him to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum. Clare never left this institution, though he wrote some of his finest poems there, including the autobiographical I Am. He died in the Asylum in 1864, aged 70.

Clare knew of Wordsworth and found his work ‘so natural and beautiful’, but Clare’s own poems challenge Wordsworth’s for their sensitivity to nature and pantheism. Clare saw God in nature everywhere: ‘I feel a beautiful providence ever about me’ he wrote in his autobiography, and it was natural for him to hold a conventional religious belief and to support the old and traditional ways, as his poems testify.

Notes by David Timson