Audio Sample

Lewis Carroll

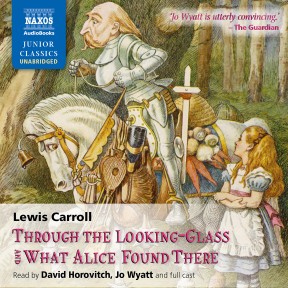

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There

Read by David Horovitch, Jo Wyatt, Rosalind Adams, Judy Bennett, Sean Barrett, Andrew Branch, Charles Collingwood, Teresa Gallagher, Steve Hodson, Nigel Lambert, Richard Pearce, Liza Ross, David Shaw-Parker, Christopher Scott, Stephen Thorne & Richard Wilson

unabridged

With a star cast including Richard Wilson as Humpty Dumpty, David Shaw Parker as Tweedledum, David Timson as the Dodo, Teresa Gallagher as the Rose and the Fawn, Sean Barrett as The Lion and many more. Alice is back in her room, stroking her cats – but not for long. Slipping through the Looking Glass she meets another wild collection of fantasy characters including the Red and White Kings and Queens, Tweedledum and Tweedledee and is entertained by the poems Jabberwocky and The Walrus and the Carpenter.

-

Running Time: 3 h 19 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-388-4 Cat. no.: NA342012 Download size: 92 MB Produced by: The Story Circle Edited by: Wolfgang Dienst BISAC: JUV007000 Released: July 2006 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Cast

- Jo Wyatt

- Alice

- Rosalind Adams

- The White Queen

- Judy Bennett

- The Red Queen

- Sean Barrett

- The Lion

- Andrew Branch

- The Guard

- Charles Collingwood

- Hatta & Unicorn

- Teresa Gallagher

- Rose/Fawn

- Steve Hodson

- Haigha

- David Horovitch

- Narrator

- Nigel Lambert

- Tweedledee/Red Knight

- Richard Pearce

- The Gnat

- Liza Ross

- Tiger Lily

- David Shaw Parker

- Tweedledum/White Knight

- Christopher Scott

- White King

- Stephen Thorne

- Old Frog

- Richard Wilson

- Humpty Dumpty

Booklet Notes

The respected author C S Lewis once stated that, ‘A children’s story which is enjoyed only by children is a bad children’s story. The good ones last.’ He continued that one should be written ‘…because a children’s story is the best art-form for something you have to say.’ Judging by these criteria, the Alice stories, having appealed to both adults and children alike for well over a century, must surely rate very highly indeed.

Lewis Carroll was the pen-name adopted by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson – a clever use of the Latin equivalents of his first names in reverse order. Born in Daresbury in Cheshire in 1832, the third child of eleven, he enjoyed entertaining his siblings with puzzles, games and puppet shows. He also enjoyed writing jokes and parodies in the family magazine. This was not an unusual activity within large families at that time and many other famous authors began their writing this way. Certainly it set the tone for later when, as an adult, he would excel at inventing fantasy worlds for an audience of children.

Lewis Carroll’s early education at home by his father, Reverend Charles Dodgson, was followed by two years at Richmond School in Yorkshire, and four years as a boarder at Rugby School. He did not much enjoy Rugby, not excelling at the sports which the school encouraged. However, he did shine academically and consequently completed his education at Christ Church, Oxford. A first class degree in mathematics won him a post as a mathematics lecturer there and he retained this position for the rest of his life.

The success of the Alice stories transformed Lewis Carroll’s life

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

brought Lewis Carroll considerable fame when it was published in 1865. The sometimes demanding vocabulary of both Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, would not have prevented younger children from enjoying the story as it was likely to have been read aloud to them in the customary Victorian way. In spite of the fame, however, Carroll valued his privacy, and at his college, where he was still known as Dodgson, he refused to accept any letters addressed to Lewis Carroll.

Behind the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, on which Lewis Carroll began work in 1869, was the original title of the sequel to Wonderland, the word Through being substituted in March, 1870. As in Wonderland, events are seen through the eyes of Alice, but this story has a dual structure of both a chess game and a mirror world. A grown-up Alice Liddell herself claimed that the chess-board idea was born at the time when she and her siblings were learning to play chess. She told how Carroll, himself a keen player and inventor of many games and puzzles, enlivened his chess games with the children by inventing imaginary conversations between the chess pieces. However, another Alice, Carroll’s cousin Alice Raikes, claimed that she was present when Carroll had the inspiration for the looking-glass theme, her cousin placing her before a mirror and pointing out how images in the mirror appear to be reversed.

Before Through the Looking-Glass itself begins Carroll includes a poem which he wrote about Alice Liddell at the time of his parting from her. In it he sadly recalls happier times when he first told her the stories included in Wonderland and Looking-Glass. The story itself charts Alice’s journey as a pawn across the chess-board to become a Queen, with the thirty-two chess pieces representing the characters in the story. Carroll lists them for readers in the Dramatis Personae before the story begins. The moves of Alice’s journey across the chess-board are also listed before the start of the story, chess experts having disagreed over the years as to whether or not such a game could in reality be played. Alice replaces the White Queen’s daughter Lily who is ‘…too young to play,’ and although chess men are usually described as being black or white, Looking- Glass pieces were called red and white, these being the colours of an ivory chess set. Because the story takes place in a looking- glass where things are reversed, the characters in the story also experience distortions of time and space. Thus the White Queen describes how time runs backwards and the Red Queen has to run in order to stay still.

Lewis Carroll, a man who liked order and control in his life, brought both his Alice stories full circle, with Alice ending up where she started. In Through the Looking-Glass this sees Alice talking to Dinah the cat and her kittens. She is wondering just who has been dreaming, and Lewis Carroll leaves his readers with this puzzle, asking: ‘Which do you think it was?’ His enjoyment of puzzles is then further in evidence in the final poem which is an acrostic: the initial letters of lines spelling out ALICE PLEASANCE LIDDELL.

Like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass contained the illustrations by John Tenniel with which we are still familiar today. It was published at Christmas 1871, although dated 1872, and the success of the Alice stories transformed Lewis Carroll’s life. It is said that he received an invitation to meet Queen Victoria and that she requested a copy of his next published work. It was quite probably a maths text book!

Of the two Alice novels, the author Virginia Woolf once said that they ‘…are not books for children; they are the only books in which we become children.’ Her meaning was that adults reading them are given a child’s view of events. Nevertheless countless children have enjoyed the stories, and with them Lewis Carroll changed children’s literature for ever: the strictly instructive themes of children’s books had been superseded, and they have become the most quoted of English novels.

Sadly Lewis Carroll was never to repeat the enormous success of the Alice stories and he lived the rest of his life in their shadow. He died in 1898 and is buried in Guildford Cemetery.

Notes by Helen Davies