Audio Sample

Classical Love Poetry

Read by Edward de Souza, Paul Jesson, Simon Harris, Karen Archer & Laura Paton

unabridged

Many of us are familiar with the epic stories and legends of the classical world. This anthology, the only one of its kind on audiobook, gives an insight into a more lyrical and tender aspect of Greek and Roman literature. From Homer’s lofty lines on the loves of the gods to the earthier verse of Catullus to his mistress Lesbia, this recording encompasses the major love poetry written between the 8th century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D. Translations are by British poets including Dryden, Pope, Johnson, Marlowe, and Byron.

-

Running Time: 2 h 18 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-1-84379-824-8 Cat. no.: NA215312 Produced by: Nicolas Soames Edited by: Jon Smith BISAC: POE001000 BIC: DCQ Released: January 1998 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

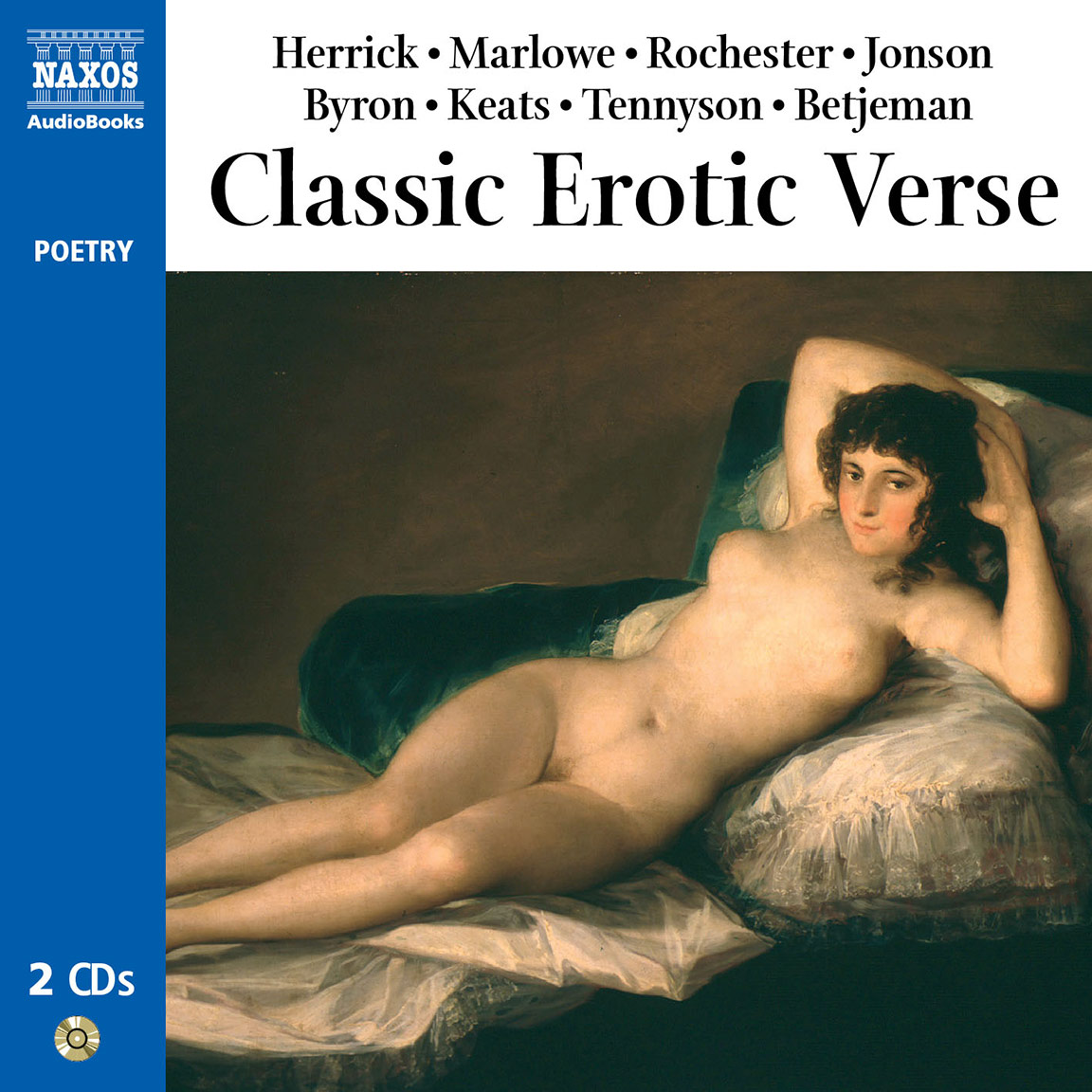

You May Also Enjoy

Booklet Notes

Greek Poetry

HOMER (fl. 2nd half of the 8th century BC) is best known as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey. It is now generally thought that both of these epic poems are the pinnacle of an age-old oral tradition. That is to say that these poems, which often repeat not only epithets (for example, Rosy-fingered Dawn), but also complete lines, were composed for recitation and were only written down at a later date.

The Iliad deals with a part of the last of the ten-year siege of Troy whereas the Odyssey, evidently intended as its sequel, depicts Odysseus’ journey from Troy back to his native Ithaca. In classical epic the gods frequently involve themselves in the affairs of men, tilting the action one way and then the other. In the first excerpt on this recording, the goddess Aphrodite (Roman: Venus) appears, disguised, to Helen urging her to repair to the chamber of her lover, Paris, who has just been whisked away (with divine intervention) from a duel with Helen’s husband, Menelaus. The second excerpt describes Zeus’ (Roman: Jupiter) seduction of Hera (Roman: Juno) while the third track depicts Hector’s poignant and final farewell to his wife Andromache. Our excerpt from the Odyssey is a poem within a poem – Demodocus, a bard in the Phaeacian court of King Alcinous, sings of Ares (Roman: Mars) and Aphrodite being caught in the midst of their lovemaking by Hephaestus (Roman: Vulcan), husband of Aphrodite.

The HOMERIC HYMNS (8th to 6th centuries BC), a body of Greek hexameter poems, were commonly attributed to Homer, although this is now considered spurious. Several of the hymns center around episodes involving a deity and the Hymn to Aphrodite tells of Aphrodite’s love for Anchises, a union that produced the founder of Rome, Aeneas.

SAPPHO (later 7th century BC) was originally from the island of Lesbos, to which she returned after a period of exile on Sicily. Much of her poetry speaks of the poet’s love for her female friends and, indeed, the island of her birth has given its name to describe female homosexuality.

ANACREON (2nd half of the 6th century BC) was born in Teos (Asia Minor) and, after migrating to Thrace and then Samos, was eventually employed by Hipparchus in Athens. Much of his poetry deals with love and is marked by a wit and simplicity.

EURIPIDES (5th century BC), along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, was one of the three great Greek tragic playwrights. It is said that he wrote 92 plays, although only nineteen of these are extant. The skeptical and radical style and content of Euripides’ writing mark a departure from the tradition of his two fellow tragedians.

THEOCRITUS (1st half of 3rd century BC) is from the Hellenistic period of Greek culture, which lasts from the early 4th to the mid-2nd centuries BC. He was the creator of bucolic (or pastoral) poetry, which was to be imitated by Moschus and Bion and, later, Virgil in his Eclogues.

MOSCHUS (fl. mid-2nd century BC) was from Syracuse and much of his poetry was written in hexameters. He often deals with the affairs of the gods or semi-gods although he also wrote bucolic poetry.

BION (fl. end of 2nd century BC) was born in Smyrna, but lived in Sicily. Most of his poetry is concerned with love, most notably his Lament for Adonis, rather than the countryside, and is both light and capricious.

ANACREONTEA is the name accorded to a body of normally slight verse, modeled on the poetry of Anacreon. Many of the poems appear to owe little to Anacreon, but have been responsible for preserving the reputation of the earlier poet.

The PALATINE ANTHOLOGY is the first of two collections of epigrams compiled in the early 10th century AD by Constantine Cephalas, an employee of the Byzantine court. Many of the epigrams, short in length, are attributed to poets from much earlier in Greek literature.

Latin Poetry

The only known composition of TITUS LUCRETIUS CARUS (98–c. 54 BC) is De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). The poem comprises six books and is an expression of the ancient and mechanistic philosophy of Epicureanism. A central tenet of the poem is that nature’s laws rule the world and that there is no afterlife – thus men need not live in fear of chastisement after death.

The output of GAIUS VALERIUS CATULLUS (c. 84–c. 54 BC) neatly splits into three groups of poetry: poems 1–60 are lyrical and short compositions encompassing a wide range of subjects; poems 61–64 are longer and in the unusual gall iambic meter, while poems 65–116 comprise elegiac verse and epigrams. The poems from the first group are delightful and many of them are to do with love, more particularly his own love for a woman identified as Lesbia (probably Clodia, sister of the disgraced statesman P. Clodius Pulcher).

PUBLIUS VERGILIUS MARO (70–19 BC) – VIRGIL – is perhaps the most famous of the poets in the circle of Maecenas, advisor to the Emperor Augustus. The Eclogues are the earliest of his three main works (Eclogues, Georgics and Aeneid) and comprise ten short bucolic poems, which owe much to the Hellenistic poet Theocritus and seem to reveal a yearning for all things rural. The four books of the Georgics are concerned with the four aspects of agriculture.

Virgil’s best-known work, the Aeneid, occupied the poet for the last ten years of his life and was actually incomplete upon his death in 19 BC. The epic owes much to Homer and is not without implicit praise of Augustus and the Pax Augusta, which the Emperor established in 27 BC (after many years of civil war). The Aeneid deals with Aeneas’s flight from the burning ruins of Troy to Italy where he is destined to found a new city – Rome. The excerpt here, from Book 4 of the poem, depicts Dido, Queen of Carthage, and her love for Aeneas – this is a particularly poignant part of the poem, as Aeneas will put his destiny before his love resulting in the queen’s suicide.

QUINTUS HORATIUS FLACCUS (65–8 BC) was also taken under the patronage of Maecenas. The first three books of his Odes were probably published in 23 BC and the fourth in c. 13 BC. The Odes are remarkable for their impeccable form and their subtle irony. The poems cover a wide range of topics touching on occurrences from the poet’s own life and those of his friends.

ALBIUS TIBULLUS (c. 55–19 BC) was a friend of both Ovid and Horace and composed two books of elegies the first of which contains mainly poems of both heterosexual and homosexual love.

SEXTUS PROPERTIUS (2nd half of 1st century BC) produced four books of elegiac poetry, the first of which won him admittance into the circle of Maecenas. This book centers on the poet’s love for Cynthia (reputedly a pseudonym for Hostia, whose identity remains unknown), a theme that permeates, albeit to a lesser extent, his later books.

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 BC–AD 17) – OVID – always stood somewhat apart from Maecenas’ circle rather aligning himself with Tibullus under the patronage of Messalla. Indeed, Augustus banished Ovid in 8 BC, possibly in connection with the prolific adultery of the Emperor’s daughter, Julia. The Amores is probably Ovid’s first body of work, closely followed by his Ars Amatoria (Art of Love) while the Remedia Amoris was probably published in AD 1 and his Metamorphoses a year later. Above all, Ovid’s verse is often entertaining and witty, but also beautifully simple and profoundly moving.

PETRONIUS ARBITER (d. AD 66) was a satirical writer thought to be associated with the court of the Emperor Nero. His best-known composition is the Satyricon, but only parts of three books of this work are extant. He also wrote a small amount of lyric and elegiac verse.

MARCUS VALERIUS MARTIALIS (2nd half of 1st century AD) is best known for his epigrams – these total more than 1,500, which were published in twelve books. His main contribution to the form of epigram was the paradoxical ‘sting in the tail’, which was to be often imitated in later attempts at the genre.

DECIUS JUNIUS JUVENALIS (fl. early 2nd century AD) was the greatest of Roman satirists. The violence of his invective and condemnations would seem to indicate a particularly bitter sentiment behind his Satires. The Sixth Satire is the most venomous of his verse and is misogynistic in the extreme, depicting the many vices of women, not least their sexual appetite.

The Meter

Both Greek and Latin meter were measured quantitatively – that is to say, in terms of the number of syllables in each line. A number of syllables make up a foot – for example, the dactyl (derived from the Greek word for ‘finger’ consists of three syllables: a long followed by two short ones). The main meters employed in the original poems featured on this recording are as follows:

Hexameter – this was the meter used in epic poetry and consists of six ‘feet’ – it is this to which Ovid alludes at the very beginning of his Amores.

Lyric Meter – this comprises Aeolic meter named after Aeolis (northern part of the western coast of Asia Minor) as used by Sappho and later by Catullus, dactylic meter, and dochmiac meter based on the dochmiac foot.

Elegiac Couplets – these consist of a hexameter followed by a pentameter. Frequently used by Propertius, Tibullus and Ovid.

The Translations

‘For this last half Year I have been troubled with the disease (as I may call it) of Translation.’

Dryden – from Preface to Sylvae

Dryden’s words give an indication of the wealth of inspiration writers down the ages have found in classical literature. The word translation actually comes from the Latin meaning ‘to carry across’ and the purpose of these translations was, indeed, not only to convey the content and essence of the originals, but also to create something of originality and extraordinary beauty in its own right.

Classical influence on English literature seems to begin in earnest with William Caxton’s indirect translation of the Aeneid in 1490. However, even in these early days there was still an ongoing debate, which has continued to rage to the present day, about how faithfully classical verse should be translated. As printed literature became increasingly popular, more and more such translations appeared, and by the latter half of the 16th century versions of Ovid, Virgil and Homer were not uncommon.

Over the centuries, different classical poets have gone in and out of fashion. Horace captured the imagination of many major writers of the 17th century while Ovid, with all his eroticism, had much appeal in the early 18th. Notably Pope himself has very often translated Homer, whom Pope describes as ‘the most ancient author in the heathen world’.

While the late 18th century, too, saw a large amount of verse translation, things classical capturing the romantic spirit of the age, the reign of Victoria proved to be a less fertile era although there was a growth in translations of prose and Greek tragedy. Our own century, too, has seen a steady flow of translation of both the epic and the lyric, most recently with Ted Hughes’s version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Notes by Anthony Anderson