Audio Sample

William Shakespeare, John Donne, Rupert Brooke, Alexander Pope, William Wordsworth & Lord Byron

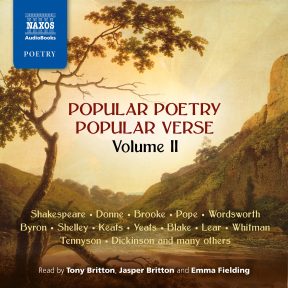

Popular Poetry, Popular Verse – Volume II

Read by Tony Britton, Jasper Britton & Emma Fielding

selections

Nearly 100 of the most popular and loved poems in the English language, this collection is one of the most comprehensive anthologies of its kind available. It covers a remarkable range, from the striking vision of Blake and Shelley and the insights of Keats to lighter but equally memorable verse by Tennyson, Donne and Edward Lear.

-

Running Time: 2 h 37 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-1-84379-630-5 Cat. no.: NA207212 Download size: 38 MB BISAC: POE001000 Released: September 2000 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Included in this title

- Sir Thomas Wyatt

- They flee from me

- Chidiock Tichborne

- Elegy before his execution

- Sir Philip Sidney

- The bargain

- Sir Philip Sidney

- He seeks inspiration

- Michael Drayton

- Since there’s no help

- William Shakespeare

- Remembrance of things past

- William Shakespeare

- The marriage of true minds

- William Shakespeare

- The expense of spirit

- King James Bible

- from the Song of Solomon

- John Donne

- The sun rising

- John Donne

- The good morrow

- John Donne

- A valediction: forbidding mourning

- John Donne

- A hymn

- George Herbert

- Prayer

- George Herbert

- Virtue

- Richard Lovelace

- To Althea, from prison

- William Blake

- The sick rose

- William Blake

- Eternity

- Robert Burns

- A man’s a man for a’ that

- William Wordsworth

- from Tintern Abbey

- Lord Byron

- When we two parted

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- To a skylark

- John Clare

- I am

- John Clare

- First Love

- John Keats

- Ode on a Grecian urn

- John Keats

- La belle dame sans merci

- John Keats

- To Autumn

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson

- Blow, bugle, blow

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson

- Break, break, break

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson

- Crossing the bar

- Emily Brontë

- Last lines

- Christina Rossetti

- A birthday

- Christina Rossetti

- Remember

- Emily Dickinson

- Parting

- Emily Dickinson

- A Narrow Fellow in the Grass

- Thomas Hardy

- In time of ‘the breaking of nations’

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- The Windhover

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- No worst, there is none

- A.E. Houseman

- Loveliest of trees

- A.E. Houseman

- Epitaph on an army of mercenaries

- W.B. Yeats

- An Irish airman forsees his death

- W.B. Yeats

- The second coming

- Edward Thomas

- Tears

- Edward Thomas

- Lights out

- T.E. Hulme

- Autumn

- T.E. Hulme

- The Embankment

- Wilfred Owen

- Greater love

- D.H. Lawrence

- Piano

- Christopher Marlowe

- The passionate shepherd to his love

- Sir Walter Raleigh

- The Nymph’s reply to the shepherd

- William Shakespeare

- Winter

- Anon

- There is a lady sweet and kind

- John Donne

- To his mistress going to bed

- Robert Herrick

- Upon Julia’s clothes

- Robert Herrick

- To Daffodils

- Sir John Suckling

- Why so pale and wan

- James Graham, Marquis of Montrose

- I’ll never love thee more

- John Bunyan

- The shepherd boy sings in the Valley of Humiliation

- John Wilmot, Lord Rochester

- Song of a young lady to her ancient lover

- William Congreve

- False though she be

- Alexander Pope

- from An essay on Man

- Thomas Osbert Mordaunt

- Sound the clarion

- William Blake

- A poison tree

- William Wordsworth

- Milton, thou shouldst be living at this hour

- Sir Walter Scott

- Innominatus

- Robert Southey

- The old man’s comforts

- Charles Lamb

- The Old Familiar Faces

- Walter Savage Landor

- Rose Aylmer

- Lord Byron

- The Destruction of Sennacherib

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- A psalm of life

- Edgar Allan Poe

- To Helen

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson

- Come into the garden, Maud

- Robert Browning

- How they brought the good news from Ghent to Aix

- Robert Browning

- My last duchess

- Edward Lear

- How pleasant to know Mr Lear

- Arthur Hugh Clough

- Say not the struggle nought availeth

- Walt Whitman

- O Captain My Captain

- Charles Kingsley

- A farewell

- Lewis Carroll

- The mad gardener’s illusions

- Thomas Hardy

- Weathers

- Ella Wheeler Wilcox

- Solitude

- Francis William Bourdillon

- The night has a thousand eyes

- Dorothy Frances Gurney

- God’s garden

- Francis Thompson

- At Lords

- Frederick Delius

- Lento, ma non troppo from ‘Two Aquarelles’

- J. Milton Hayes

- The green eye of the yellow god

- A.E. Houseman

- When first my way to fair I took

- Sir Henry Newbolt

- He fell among thieves

- Rudyard Kipling

- Gunga Din

- W.B. Yeats

- The lake isle of Innesfree

- Alan Seeger

- Rendezvous

- Laurence Binyon

- For the Fallen

- Rupert Brooke

- The Old Vicarage, Grantchester

Booklet Notes

Verse of some kind seems to be common to all historical cultures. It begins as a craft, a way of ordering knowledge and experience for easy memorising and maximum impact.

However, as it is practised for its own sake it becomes something more. The play of sound and rhythm with observation and narrative, of vocabulary and syntax with thought and feeling and metaphor, can develop such a grace and complexity and precision that we have to call it something different. It becomes poetry. And of all the languages of the world, English is, by common consent, the richest and most deeply worked mine for this most precious commodity.

However, not all the verse that sticks in the mind is twenty-two carat poetry. Some of our best loved versifiers – notably Victorian ones – indefatigably shovelled out irredeemably low-grade ore which they fashioned into inspiring, moralising or sentimental recitation pieces. These became, however, so highly valued that they have acquired the warm and glowing sheen of sheer familiarity. They constitute, in fact, some of our favourite verse. Children used to be made to learn them by heart, and somewhere in the mind, if not the heart, they remain. This is, after all, what verse is designed to do – to be remembered.

The result is that while our poetic tradition has its roomfuls of glass fronted display cabinets crammed with priceless heirlooms, it also has its lumber room. And sometimes the lumber room is where we want to be – turning up dusty, half-forgotten toys and treasures and nick-nacks, long-neglected but once lovingly displayed on a crowded mantelpiece.

For this collection we have dusted down a few of these old favourites from the lumber room, but at the same time we have had to recognise that some of them show their age, and don’t appear to their best advantage alongside the real collectors’ items, the pieces that are quite untouched by time. Further, the effect of time on some of the poetic brassware of the Victorian age is that it leaves on it quite a nice verdigris of irony. And while this irony is an essential part of our appreciation of these very heavy pieces, we don’t want it to spread and interfere with the finely balanced and delicately traced effects of the real poetry.

So instead of organising this anthology alphabetically or altogether chronologically, or even according to subject matter, we have taken the unfashionable step of dividing up our material according to the poetic ambition and achievement embodied in each piece. To the lumber room collection we have added lightweight verse from earlier ages, together with one or two classic examples of what is called ‘light verse’. This then leaves the poetry which really is in a class of its own – but also carried in our minds as half-remembered scraps – where it belongs: in a class of its own.

As with all such principles of organisation there are borderline cases which in themselves might seem to make a nonsense of the whole exercise, particularly perhaps with the Elizabethans. However, the great poets who kick off the ‘favourite verse’ collection – Marlowe, Raleigh and Shakespeare – are here in relaxed, expansive mood. By contrast, the otherwise unknown poet Chidiock Tichborne, whose ‘Elegy’ opens the batting for the ‘favourite poetry’ collection along with another poet who faced execution on the block, Thomas Wyatt, well illustrate Dr. Johnson’s maxim that death concentrates the mind wonderfully. Our hope is that these two collections, in their different ways, will remind the listener of at least some of the rewards and pleasures we have inherited in our great poetry and our splendid verse.

Notes by Duncan Steen