Audio Sample

Jalaloddin Rumi

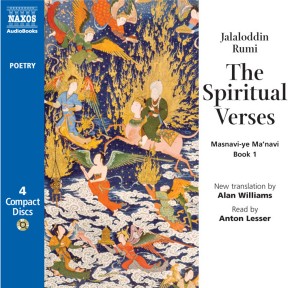

The Spiritual Verses

Read by Anton Lesser

abridged

Rumi’s Spiritual Verses, is the greatest mystical poem in Islamic culture and of all time. Rumi tells of our human separation from reality, from love and from truth. He shows how love – neither erotic nor sentimental but divine, by which the universe is held together – enlightens ignorance and dissolves suffering. The first book of the Masnavi is the key to the whole work: it takes off from simple, amusing tales into realms unimaginable, but wholly familiar to the human heart.

-

Running Time: 4 h 44 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-669-4 Cat. no.: NA446612 Download size: 69 MB BISAC: POE013000 Released: September 2007 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Reviews

This volume contains a dozen stories from Book One of the six-volume collection, composed in rhyming couplets by the Afghan/Persian poet Rumi in the 1260s. With Anton Lesser’s patient, precise narration, and Naxos’s quality production, these religious stories are accessible to a wider audience. Without being effeminate, Lesser’s voice is unusually high pitched for a man’s voice, which may be jarring at first for some listeners. But his classical but unpretentious Shakespearean style, perfectly paced, makes this set worthy of repeated listening. Persian music, commissioned for this recording, sets the tone. The liner notes include background to the work and an introduction by the translator.

S. E. S., AudioFile Magazine

Booklet Notes

The Spiritual Verses – Masnavi–Ye Ma‘Navi Book 1

An Introduction by Dr Alan Williams

The Sufi poet Jalaloddin Rumi was born in 1207 in a small town near Balkh in present-day Afghanistan. His family had to flee the advancing Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan who by 1220 had devastated Balkh and Samarqand, the cities of Rumi’s childhood. Rumi’s family settled eventually in Konya, in central Anatolia (now in modern Turkey), in a province that was still known as ‘Rum’ (Rome / Byzantium) as it had only recently been conquered by the Muslim Seljuqs. Rumi is now claimed by several nations as their own poet – Afghanistan (because he was born in that region), Iran (because he wrote in Persian) where he is known as Mowlana Balkhi (‘Our Master of Balkh’), and Turkey (because he spent most of his life in Konya, Turkey) where he is known as Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi. Nowadays, as UNESCO designates 2007 the Year of Rumi in his 800th anniversary year, he is also claimed by the world and is known as Rumi.

Rumi’s father Bahaoddin Valad was a learned religious scholar and Sufi (a follower of the spiritual path of Islam), and Rumi himself was educated to a high level in Aleppo and Damascus. There he was taught by the foremost scholars and Sufis of the time, including, it is said, the great mystical philosopher and visionary Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi. Rumi succeeded his father at a madrase (college) in Konya but continued to undergo a lifelong spiritual education under a series of teachers. The most intense period of Rumi’s life began in 1244 when he met Shamsoddin of Tabriz, a deeply learned scholar and wandering mystical adept of the highest attainment. Shamsoddin was in his sixties when he arrived in Konya: Rumi spent a great deal of time with him for four years until Shamsoddin disappeared as suddenly as he had arrived in Rumi’s life. Shamsoddin had recognized early on that Rumi was destined to exceed his own spiritual attainment on the Sufi path. Rumi had already become famous for his composition of a large body of thousands of lines of sublime lyric poetry which is collectively known as the Divan of Shams of Tabriz, by which Rumi pays his teacher the ultimate compliment of surrendering his very own name. In addition to his Masnavi, Rumi also wrote several prose works, of talks, letters and sermons. It is to the Masnavi, however, that we turn for an outpouring of Rumi’s most mature and sustained mystical teaching.

The Masnavi-ye Ma‘navi ‘The Spiritual Verses’ is the longest and most celebrated mystical poem in Persian. Written in the 1260s, the Masnavi has had more influence in Islamic culture than any other work except the Qur’an, indeed it was dubbed ‘the Qur’an in the Persian tongue’ by the 15th century poet Jami. It is written in six books totalling some 26,000 couplets, of which the first book (of 4,018 couplets) is featured in abridgement in this recording. The Masnavi is a work of enormous proportions and spiritual dimensions, but its purpose is ineffably singular: to enable the reader and listener to progress to the ultimate goal of union with God. For Rumi and the particular Sufi tradition to which he belonged, God is known primarily through, indeed God is, the source and quintessence of love. The human heart must be opened to perceive this ultimate and all-powerful love with the ‘eye of the heart’. What blinds this inner eye is the self (Persian and Arabic nafs) that keeps us locked in the prison of our sensual nature and restricts growth to our full potential as human beings. Rumi’s Masnavi engages directly with every new reader and listener to coax them to think and feel beyond the sensual world of appearance: the stated goal is that in the mirror of the heart, we come to reflect the beauty and perfections of God in the world.

As I have explained in the Introduction to my full translation of the first book of this great poem, the Masnavi is a polyphonic composition, like a stage drama of many voices. Yet it has no framing plot. Its many stories are all a plot, i.e. a strategy to hook our imagination and take it somewhere beyond itself. Rumi’s stories are taken from countless sources – from scripture, literature and folk tales – but in each he quickly subverts the narrative as he transports the listener to his own purposes. I have described the Masnavi as constantly spiralling within a sevenfold register of ‘voices’. These are all addressed to you (the listener) and You (God). The shifting of perspectives through the changing of voices is virtually seamless: the effect is that, having lulled us into his stories, Rumi breaks off into ever-intensifying meanings, which we absorb as if by osmosis. The seven principal voices, like the notes of an octave, are as follows The authorial voice is one we hear most clearly in passages such as The Song of the Reed and the Central Discourse – this voice resonates with the authority of the pir or Sufi elder and addresses You, God, and you, all of humankind.

The storyteller voice begins each of the twelve stories in this recording – it is lively and witty, but soon may modulate into the next voice. It is always interrupted by one of the following voices.

The analogical voice seems to distract from the narrative, but in fact Rumi is here grabbing examples out of thin air to illustrate his meaning.

The voice of speech and dialogue: these are the voices of the many characters who populate his stories. Most crucially, in this voice, Rumi is easily able to slip into the next voice.

The voice of moral reflection is identifiable by its chiding tone and imperative mood. Most often, however it is only a means of transition into the next voice, which for Rumi’s readers and listeners is the most sought after.

The voice of spiritual reflection: this voice is addressed to God on a ‘vertical’ trajectory of flight from this limited world to absorption in the ecstatic state beyond. It is as if each couplet is no sooner pronounced than it is expendable and replaced, like an impassioned cry or plea as if the poet is drowning or soaring to express the passion he feels for the divine Beloved. Inevitably this voice falls into silence.

The last principal voice I identify in the cycle I call hiatus, for it is a point of aporia or impasse, beyond which one cannot speak outwardly. It signals the limit of Rumi’s discourse in words and the beginning of the listener’s experience of silence. As he says just a few lines after he has begun the Masnavi:

The raw can’t grasp the state of one who’s cooked,

so this discussion must be brief – farewell!

This Abridgement

This abbreviated version of the poem is a reduction from over 80,000 to 32,000 words. Twelve stories from the first book have been included, including one of the longest in the whole Masnavi, namely, The Caliph and the Bedouin. Some of the stories that do not appear were excluded because their reference and subject matter would be obscure to an audience unfamiliar with the Qur’an. However, in the remaining twelve I have not filleted out the ‘difficult passages’ from the stories, but tried to allow Rumi’s own didactic, polyphonic structure to remain intact.

Alan Williams