Audio Sample

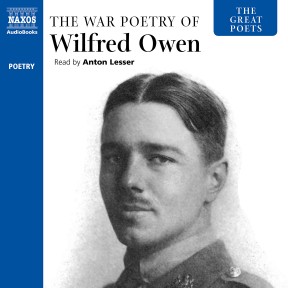

Wilfred Owen

The Great Poets: The War Poetry of Wilfred Owen

Read by Anton Lesser

unabridged

No poet is more closely identified with the First World War than Wilfred Owen. His striking body of work, grim to the point of brutality yet, at the same time, majestic and awe-inspiring, defines the war for us. It is in each of these famous poems that Owen reflects on the four terrible months that he lived through; he conveys the experience of war, the death, the destruction and the filth, through a unique poetic language and a bold artistic vision. This anthology collects 49 of Owen’s iconic poems and serves not only as a perfect introduction to his verse but also as a commemoration of the sacrifice that was made by an entire generation of young men.

-

Running Time: 1 h 19 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-1-84379-774-6 Cat. no.: NA0150 Download size: 21 MB BISAC: POE005020 Released: November 2013 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Included in this title

- Preface

- From My Diary, July 1914

- 1914

- The Send-off

- The Letter

- Arms and the Boy

- Parable of the Old Men and the Young

- Spring Offensive

- The Chances

- Futility

- S. I. W. Self Inflicted Wound

- Has Your Soul Sipped?

- As Bronze May Be Much Beautified

- It Was a Navy Boy

- Inspection

- Anthem for Doomed Youth

- The Unreturning

- Le Christianisme

- Soldier’s Dream

- At a Calvary Near the Ancre

- Greater Love

- The Last Laugh

- Hospital Barge

- Training

- Schoolmistress

- An Imperial Elegy

- The Calls

- On Seeing a Piece of Our Artillery Brought into Action

- Exposure

- Asleep

- The Dead-Beat

- Mental Cases

- Conscious

- The Show

- Smile, Smile, Smile

- Disabled

- A Terre (Being the philosophy of many soldiers)

- Beauty (Notes for an Unfinished poem)

- Miners

- Cramped in That Funnelled Hole

- The Sentry

- Dulce et Decorum est

- Apologia pro Poemate Meo

- Insensibility

- The End

- The Next War

- Sonnet to My Friend – With an Identity Disc

- Strange Meeting

- On My Songs

Reviews

As the big anniversary approaches, the great Anton Lesser takes honest realism to new heights with his intelligent, movingly understated reading of The War Poetry of Wilfred Owen. As Owen himself recognised, ‘the poetry is in the pity’. Nobody could listen to these poignant, anguished elegies all at once, without helpless tears. I know. I tried.

Sue Gaisford, The Independent

These 49 poems show what Owen intended: the pity and truth of war. The Parable of the Old Man and the Young re-works the story of Abraham and Isaac. Owen’s ‘old man’ refuses to slay the ‘Ram of Pride’ and instead kills ‘his son / And half the seed of Europe, one by one’. All are enhanced by the infinitely sympathetic reading, but the force of anger beneath the understatement makes the one, for me, the most memorable.

Rachel Redford, The Oldie

Booklet Notes

It would surely be impossible to name a poet more closely or completely identified with any historical event than Wilfred Owen is with the First World War. In some ways he has actually come to define that war for us, along with images of the trenches, along with names like the Somme and the Marne, with the faces of Lord Kitchener and the Kaiser, and with the endless, uniform, silent ranks of graves in the cemeteries of Northern France. In the English mind, Owen’s words – grim to the point of brutality, yet, at the same time, majestic and awe-inspiring – form the definitive memory of a conflict that was too terrible for rational analysis or common speech. Among all the poets of the war, Sassoon, Graves, Rosenberg, Herbert Read, David Jones and others, Owen’s voice is the one that embodies the most utter commitment – commitment to witness and report faithfully on the horror of omnipresent death, and commitment to protest against it with all the anger he could command.

Because of this complete identification with the war, and because he died young, Owen as a man is not easy for us to know. Born in Shropshire in 1893 into a lower middle-class family, the strongest childhood influence on him was his mother’s devout Christianity. Although a clever child, he narrowly failed the entrance examinations for university. Soon after leaving school he settled in Bordeaux as a teacher of English. His twenty-first birthday had fallen in April 1914, and during his period in France he had already formed the resolve to devote his life to poetry, which he had been writing for some years. In 1915 he returned to England to enlist in the army. After his military training he was in the front-line trenches from January to April 1917, when he was invalided home with what was then called shell-shock, but which we would now call post-traumatic breakdown. In a military hospital he met and came strongly under the influence of Siegfried Sassoon, and in this period of slightly more than a year, he wrote all his famous war-poems through an act of memory and reflection on the horror of the four terrible months that he had lived through. Deemed to have recovered, he was sent back to France in September 1918 and was killed in November, only days before the armistice came into force.

When he died, Owen was entirely unknown to the public as a poet. It was two years later that his first collection was published and his reputation grew steadily thereafter. It is probably fair to say that Benjamin Britten’s decision to set his poems to music in his War Requiem of 1961 marked the arrival of Owen as a major figure in English literature. For that collection which he never saw, Owen had composed a Preface that became almost as famous as the poems:

This book is not about heroes. English poetry is not yet fit to speak of them. Nor is it about deeds, or lands, nor anything about glory, honour, might, majesty, dominion, or power, except War. Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.

Radical, challenging and memorable as these words are, they are nevertheless misleading, for the truth is that Owen was concerned with poetry, for he laboured long and hard to concentrate the horrors of war into a language that was powerful and musical, shocking yet intricately crafted at the same time. He chose the medium of poetry, not the cold factual report, precisely because he wished to re-create the true experience of war – the death, the destruction, the filth, and the sense of overwhelming rage that he felt. What he meant when he said ‘I am not concerned with Poetry’ was that these experiences had cleansed him of the youthful, sentimental neo-Victorian view of poetry which he had started with, and which had given him a new vision of what poetry might be, and a new language in which to embody that new vision.

In exploring these previously unknown realms, Owen approached his task in a number of ways and employed a number of distinct strategies. The most obvious is the elaborate violence with which he mirrors the physical horrors of the war in his imagery of broken bodies and filthy, torn flesh. The vehemence of this language was something new in English Poetry, and even now, almost a century later, it is not easy to read, above all in Dulce et Decorum Est. This vehemence merges into his anger at the political masters who had loosed this horror on the world, and at the culture of obedience that sustained it. This social anger also fuels the savage irony with which he subverts the lies told at home in England about the war, often in poems that use the coarse speech of the common soldier. In complete contrast are the poems which are dominated by pity, where the poet’s voice is grave and quiet, dispassionately parading before us the shattered victims of war, the soldiers now crippled in mind and body, poems such as Disabled or Mental Cases, the last as painful to read as certain passages from King Lear. Controlled rage, to the point of nihilism, runs through all these poems, linked to Owen’s obvious loss of his youthful religious faith. Now he sees the world as ruled by a savage god who exercises arbitrary and pitiless power over his creation, killing at will and without reason. Finally, beside the pity, there is a certain unmistakable tenderness for the young men who suffer and die so needlessly, their innocent lives the sacrifices demanded by the demonic powers who are driving the war forward. There is some slight evidence that Owen may have been homosexual, and that this tenderness had emotional roots within his personality. If true, this may perhaps answer the puzzling question of why Owen, feeling as he did about the war, returned to the front: it may have been a gesture of pity and of solidarity with his fellow men, his fellow victims.

Through all these strategies, and through the controlled passion of his language, Owen’s small body of verse has achieved a historic importance. These poems could not mend the broken bodies about which Owen wrote, but to some extent, because they told the truth, they could and did help in healing the minds of those who had lived through the war. Just one critical question remains about Wilfred Owen: does he exist as a poet outside the experience of the First World War? Obviously not; obviously his subject matter and his language are both identified exclusively with that War, and for this reason he cannot truly be called a major poet. But he is a powerful and arresting figure, whose personal response to the war will always be part of humanity’s collective memory, while the emperors, the politicians and the generals behind it all have long ago stiffened into the despised, blind, autocratic figures whom we now encounter in history books. This was the young poet’s belated victory over the masters of war. It’s true that Owen’s life and his art were both incomplete, they were cut short; but in this he represents the entire generation of young men whose sacrifice is commemorated in his work.

Notes by Peter Whitfield