Audio Sample

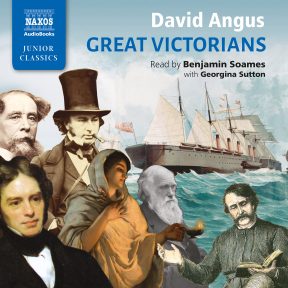

David Angus

Great Victorians

Read by Benjamin Soames with Georgina Sutton

unabridged

The Victorian era was a time of great change and rapid progress. Britain was undergoing the most tremendous development. Scientific discoveries had prompted the Industrial Revolution, which made Britain the world leader in iron and steel production. Science was undergoing a revolution, enabled by the groundbreaking work of Michael Faraday, who led the Royal Institution. Great swathes of Central Africa were mapped by the explorer David Livingstone and the understanding of humankind’s place in the world was being redefined by the theories of the great naturalist Charles Darwin. Brunel’s steam-driven ships were connecting continents and Florence Nightingale’s work in hospitals helped lay the foundations for modern nursing. In literature, Charles Dickens put the lives of ordinary men and women at the centre of great novels for the first time, and in politics Britain was completely transformed by the reforms of William Gladstone. Written exclusively for Naxos AudioBooks, Great Victorians captures a fascinating period in world history.

-

Running Time: 2 h 34 m

More product details

Digital ISBN: 978-1-78198-099-6 Cat. no.: NA0292 Download size: 59 MB Produced by: Nicolas Soames Edited by: Sarah Butcher BISAC: JNF007020 Released: July 2018 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Booklet Notes

Alexandrina Victoria was born on 24 May 1819, at Kensington Palace in Hyde Park, in London. On 20 June 1837 her uncle, King William IV, died. As he had no children of his own, she succeeded him as Queen Victoria. She was just eighteen years old.

Victoria had a rather miserable childhood. She was bullied by her domineering mother, who had plans to control her and to rule in her stead. When she was eighteen, however, Victoria gained her independence, and she found lasting happiness in her role as Queen, which she took very seriously. On 10 February 1840, her joy was complete when she married her German cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Over the centuries royal weddings have nearly always been arranged to make political alliances, and their marriage was no different. Despite this they were truly devoted to one another. They went on to have nine children, and were hardly ever apart until Albert died of typhoid fever in 1861. The grief-stricken Victoria was to rule for a further 40 years. Hers was the longest reign of any British monarch until her descendant Queen Elizabeth II overtook her in 2015.

Some violently objected to all the rapid changes in society, while others thought that change should move faster.

After Prince Albert died Victoria did not marry again, and she stayed in mourning for the rest of her life. This is why she is generally pictured wearing black. In those days the behaviour of the Royal Family, and indeed even the way they dressed, tended to set the tone for the whole of society. The kings who had preceded Victoria had led rather wild and extravagant lives,

so British society had tended to reflect that. Now Victoria, with her passion for family life, respectable behaviour and her devout Christianity, encouraged new, more serious fashions.

To later generations this came to seem a bit pompous and even dishonest. Seventeen years after Victoria’s death, the writer Lytton Strachey wrote a popular book called Eminent Victorians. The title was ironic because the book mocked the people it pretended to praise. One of them, Florence Nightingale, who appears in this book, was a particular icon of the Victorian age and a personal friend of the Queen, so she must have seemed an easy target. Strachey’s view of the Victorians as hypocrites, merely pretending to be virtuous, became so popular that for many people it became the defining characteristic of the age.

However, although it is easy to scoff at what seem like the pretensions of that time, it is undeniably true that the people who shaped that age and who are described in this audiobook shared one great virtue: energy.

The Victorian era was a time of great change and prosperity. Britain was undergoing the most tremendous development. Scientific discoveries had prompted the Industrial Revolution, which had made Britain the world leader in iron and steel production. Science itself was undergoing a revolution, celebrated by the groundbreaking work of the Royal Institution, which was led for part of Victoria’s reign by the brilliant Michael Faraday. Even the understanding of humankind’s place in the world was being redefined by the theories of the great naturalist Charles Darwin.

Factories powered by British steam engines were creating huge fortunes. Trade was booming. Cheap raw materials poured into Britain, and British factories transformed them into valuable goods, which were then exported all over the world. This explosion of power and progress was celebrated at the first World Fair, the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851. The brainchild of Prince Albert, it fired the imagination of the public, and for many people it came to symbolise the Victorian age. Over six million people visited the Crystal Palace, a figure equivalent to a third of the population of Britain at the time.

The new towns that grew up around industrial centres quickly grew into major cities. The large numbers of people who poured into these places demanded a voice. In literature, in the works of Charles Dickens, the lives of ordinary men and women became the central stories of great novels for the first time.

Furthermore, the political map of Britain was completely transformed in Victoria’s reign. When she came to the throne, virtually all the power in the country was concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy men. In a country of 18 million people, fewer than 750,000 were eligible to vote. Most of them voted as they were told to by the landed gentry who owned the constituencies that were represented in parliament. By the last general election of her reign, in 1900, over three and half million votes were cast. The principal architect of this change was the champion of reform, William Gladstone, who served as Prime Minister four times in Victoria’s reign.

Communication between cities was greatly accelerated by the development of the railways, in particular through the work of the great engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Brunel’s steam-driven ships then began to connect continents. His huge ship Great Eastern laid the first transatlantic cable connecting Britain to the United States in 1858. By the end of Victoria’s reign cables had been laid all over the world, and it was possible to send telegraphic messages all around the British Empire. For indeed, Britain had greatly added to its empire. Apart from Great Britain and Ireland, Victoria ruled Canada, Australia, South Africa, Malaysia and parts of the West Indies. Great swathes of Central Africa were mapped by the explorer David Livingstone, and much of this too would soon be gobbled up by the ever-expanding British Empire. In 1857, after a bitter struggle, what is today India and Pakistan fell under the authority of the British crown, and Victoria was declared Empress of India.

Through all this the Queen was not always popular. Particularly after Albert’s death, when she practically retired from public life, she became a rather remote figure. Some people thought there should be no Empire. Some violently objected to all the rapid changes in society, while others thought that change should move faster. A few directed their anger at the Queen. There were no fewer than eight attempts to assassinate Victoria. However, when this happened it seemed to rally the country around her. ‘It is worth being shot at to see how much one is loved,’ she once said.

For 40 years of her reign Alfred Tennyson served as the Poet Laureate. And although there were certainly some ups and downs in her relationship with her subjects, for the most part it seems that the British people agreed with the sentiments expressed in the poem Tennyson wrote for Victoria’s Jubilee in 1887:

Fifty times the rose has flower’d and faded,

Fifty times the golden harvest fallen,

Since our Queen assumed the globe, the sceptre…

Nothing of the lawless, of the despot,

Nothing of the vulgar, or vainglorious,

All is gracious, gentle, great and queenly

Notes by David Angus